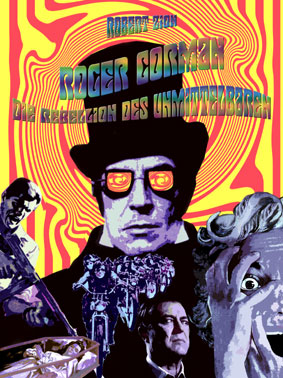

Surrealism & My Films

by Roger Corman (translated by Jim Knox)

(Click here for printer-friendly version)

Translated by Jim Knox from the French. Originally published in Etudes Cinematographiques # 41/42 (1965) "Surrealisme et Cinema"; Yves Kovacs, editor. Copyright, Jim Knox 2001

The most interesting aspect of surrealism resides, to my mind, in the attempt to describe the machinations of the subconscious, and its influence upon conscious perception. Within the dimensions of this process is a permanent phenomenon, that of the subconscious, and to my mind, expressing visually more than verbally, the possibilities of the cinema are the perfect means for expressing this surrealist ideal. In America, more than elsewhere, the word surrealism has retained its original association with painting. But a painter can only depict a moment in time; I'm more influenced by those writers who describe and interpret, in a very precise fashion, what proceeds from the subconscious mind.

Two

writers possess a pivotal influence.

Edgar Allan Poe and Franz Kafka aren't

commonly considered to be surrealist

writers. But the fact that the world,

perceived and reflected through their

subconscious, has become a different

world for their readers, provides

me an example of the supremacy of

a surrealism which will illustrate

dynamics (in the sense that it

Two

writers possess a pivotal influence.

Edgar Allan Poe and Franz Kafka aren't

commonly considered to be surrealist

writers. But the fact that the world,

perceived and reflected through their

subconscious, has become a different

world for their readers, provides

me an example of the supremacy of

a surrealism which will illustrate

dynamics (in the sense that it  shows

the subconscious in action), over

a "certified" surrealism (which is

content to show us that the subconscious

exists).

shows

the subconscious in action), over

a "certified" surrealism (which is

content to show us that the subconscious

exists).

As

to how this concerns my own films,

I don't think they properly qualify

as purely surrealist. They're approaching

surrealism. I'm always trying, in

my work, to illustrate the conscious

life of the individual and explain

how that life is influenced by the

subconscious. Accordingly, I explore

the frontier between the real world

and the fantastic, and show that,

while these worlds are very different,

they nevertheless influence one another.

To give an example of this subconscious

activity: I've often used the dream,

in order to establish clearly that

we've left behind the real world and

entered into the fantastic world of

the spirit. And yet, the real world

is equally influenced by our subconscious.

The clothes we wear, or the house

we live in, the life we lead; everything

is influenced by our subconscious

as

well as our conscious mind, so by

photographing the concrete objects

of the our real world and our relationship

to them, we photograph a part of our

subconscious, to the extent that it

determines our universe. If, for example,

we show a man in a red sports car,

that he chose among many others, and

it drives, very fast, along a winding

mountain road punctuated by tunnels,

we express a part of his unconscious

desires. But, right now, we show the

car and the mountains as they are.

If we photograph them through a red

filter, we emerge from reality to

enter into a fantastic universe. This

distinction is very important to me.

as

well as our conscious mind, so by

photographing the concrete objects

of the our real world and our relationship

to them, we photograph a part of our

subconscious, to the extent that it

determines our universe. If, for example,

we show a man in a red sports car,

that he chose among many others, and

it drives, very fast, along a winding

mountain road punctuated by tunnels,

we express a part of his unconscious

desires. But, right now, we show the

car and the mountains as they are.

If we photograph them through a red

filter, we emerge from reality to

enter into a fantastic universe. This

distinction is very important to me.

True surrealism is more akin to fantasy, or the world of dream, where we observe the subconscious directly in action; while a variation of surrealism deals with the real world, where the effects of the subconscious are described indirectly. That pure surrealism is a very powerful domain, but the limits I'm obliged to observe in my work - also powerful! - compel me to explore the broader terrain of an indirect surrealism. One and the other seem to me equally useful, and the choice is determined by necessity and opportunity.

Another question has always interested me. That's the problem of knowing to what extent the artist's work is at the control of their spirit. One makes a conscious attempt to express with the symbols of our subconscious, but what we know is so tiny, its inevitable that a major part of the work is unconscious, and that someone will find powerful significances where the author doesn't. These significances will be valid, just the same.

Roger Corman is the Director of almost one hundred feature films; among them, "A Bucket Of Blood", "The Pit And The Pendulum", and "De Sade". Through his production and distribution interests he championed the early careers of Nicholas Roeg, Martin Scorsese, Paul Bartel, Joe Dante, and very many others. His autobiography is "How I Made A Hundred Films And Never Lost A Dime".