Moving Objects: The Projected Image in the Gallery Space

by Terri Cohn

"In the closed space of cinema there is no circulation, no movement, and no exchange... This model is broken apart by the folding of the dark space of cinema into the white cube of the gallery." - Chrissie Iles Into the Light: The Projected Image in American Art, 1964–1977

The exchange of meaning and eradication of fixed boundaries among artistic media and disciplines has been an area of critical investigation since the early 1960s. During the 1960s and '70s, artists working with the perceptual vocabulary of Minimalism achieved the final dismantling of linear perspective and notions of a fixed position for the viewer, and began to posit a phenomenological experience of objects in relationship to architectural space. As part of this process of creating a new language of representation, artists began to work with time-based media, including film, slides, video, and holographic and photographic projections, as means to transform viewers' perceptions of physical space. Through this active engagement of the viewer and dismantling of our notions of immutable visual and material relationships (exemplified by the experimental sculptural and film installations of artists such as Robert Morris), the gallery space was transformed into a perceptual field.

The introduction of a temporal element into the experience of the art object and of the relocated focus of the viewer from object to gallery space was expanded in the 1960s by Morris and other Conceptual art pioneers like Bruce Nauman. Their investigations were an extension of a lineage that can be traced to Marcel Duchamp's experiments with multiple perspectives, lenses, perception, and the moving object in the early 20th century. This historical link extends back in time through Eadweard Muybridge's photographic motion studies in the 19th century to the camera obscura, which was mentioned as early as the fifth century BC. Leonardo da Vinci's notebooks actively describe a fascination with the moving image in a darkened chamber, and such spaces were built and used to observe projections of the heavens by the 16th century. In his recent film Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, David Hockney demonstrated that some of the world's most famous painters historically used optics—mirrors and lenses (or a combination of the two)—and the camera obscura to create their masterpieces. Consistent throughout this evolution is the interest in recording a mutable image by capturing light within a darkened room, which is not only a fundamental human fascination but also has a palpable relationship to the physiology of vision, as images appear upside down in the retina and are inverted by the brain.

These explorations of a space otherwise invisible to the viewer are revealed and mimicked in film and video. Simulation of the myriad number of angles contained in a viewer's circumnavigation of an object are made possible by these media. Building off this knowledge as well as the conceptual and process-based outcome of Minimalism, a growing number of recent artists and filmmakers have focused on the interrelationship between their media and film/video, with the intention of expanding the experience and potential of both. Complementing this area of inquiry, recent experiments with the projected image in installation and sculptural contexts reveal that the parameters and possibilities of this relationship also have deep psychological and emotional meaning.

The breadth

of recent work in this area is vast and international, which makes the

writing of an exhaustive treatise on the subject impossible. However,

a discussion of some recent projects and approaches provides insights

into certain concerns of video artists and filmmakers working with this

hybrid cognitive medium. The timing of this discussion is unusually germane,

because of the extensive crossover interest among artists and filmmakers

demonstrated in recent museum exhibitions, such as Matthew Barney's Cremaster

cycle at the Guggenheim Museum, a spectacularly scaled installation (and

series of films), which was aesthetically influenced by cinematic staging,

pacing, and theatrical potential; and James Turrell's Into the Light,

at the Henry Art Museum, University of Washington, Seattle. Although he

created this ethereal, light-infused room without projection, Turrell

challenged viewers' spatial perceptions by creating the illusion of a

wall at the interface of fluorescent and neon lighting. On a more intimate

scale are installations such as Bill Viola's Memoria, part of the

permanent collection at the San Jose Museum of Art, which features a suspended

Shroud of Turin-like silk panel, onto which a projected image of a face

gradually articulates the range of human expressions of emotion; and the

works by filmmakers Eija-Liisa Ahtila, Atom Eyogan (in collaboration with

Juliao Sarmento), and Abbas Kiarostami included in Reel Sculpture:

Film Into Art, at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

The breadth

of recent work in this area is vast and international, which makes the

writing of an exhaustive treatise on the subject impossible. However,

a discussion of some recent projects and approaches provides insights

into certain concerns of video artists and filmmakers working with this

hybrid cognitive medium. The timing of this discussion is unusually germane,

because of the extensive crossover interest among artists and filmmakers

demonstrated in recent museum exhibitions, such as Matthew Barney's Cremaster

cycle at the Guggenheim Museum, a spectacularly scaled installation (and

series of films), which was aesthetically influenced by cinematic staging,

pacing, and theatrical potential; and James Turrell's Into the Light,

at the Henry Art Museum, University of Washington, Seattle. Although he

created this ethereal, light-infused room without projection, Turrell

challenged viewers' spatial perceptions by creating the illusion of a

wall at the interface of fluorescent and neon lighting. On a more intimate

scale are installations such as Bill Viola's Memoria, part of the

permanent collection at the San Jose Museum of Art, which features a suspended

Shroud of Turin-like silk panel, onto which a projected image of a face

gradually articulates the range of human expressions of emotion; and the

works by filmmakers Eija-Liisa Ahtila, Atom Eyogan (in collaboration with

Juliao Sarmento), and Abbas Kiarostami included in Reel Sculpture:

Film Into Art, at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

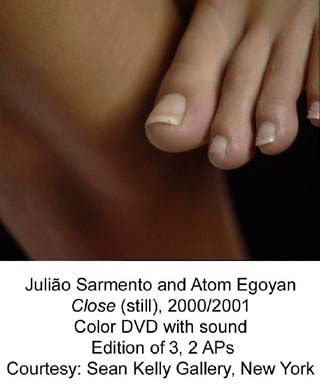

Of the three installations in this latter exhibition, the most sculptural is Kiarostami's dream-like Sleepers - largely a result of its high-contrast resolution - in which a life-sized sleeping couple is projected on the floor. As we observe the occasional movements and slow tempo of the pair's stirrings in alliance with its setting, an engaging sense of realism and surrealism simultaneously emerges, questioning the voyeuristic position of the viewer. This positioning is also a powerful component in Egoyan and Sarmento's Close, which forces the viewer into immediate physical proximity with the 157.5" by 236.25" screen installed in a narrow corridor. This proximity intensifies the narrative play between magnified hands clipping toenails that fall, individually, onto a woman's tongue, and the soothing voice recounting scary foot stories. The palpable tension this tactic creates, in combination with the film's slow-motion effect (seemingly created in post-production), forces audience members to decide where to position themselves physically, and whether to stay to experience the outcome of this bizarre parable.

These

works raise questions about the choice and arrangement of the gallery

space and the motivation for manipulating the time of the projection,

which determine the engaged dialogue between the projected image and its

recipient surface. This exchange is also among Lynn Marie Kirby's primary

concerns, apparent in her performance-based works such as Twilight's

Last Gleaming, part of the S.F. Cinematheque's 2002 retrospective

of her work held at the San Francisco Art Institute and Yerba Buena Center

for the Arts. Because she is interested in the dynamics of viewing, Kirby's

work is directed in part at deconstructing the theatrical space. This

piece commented on the contemporary political climate and the ways in

which artists have talked about national history in their work. Twilight

was visually driven by the shifting pacing of music such as a quick-tempo

John Philip Sousa march and Jimi Hendrix's Star Spangled Banner,

which "stretched out the gesture" (a reference to how she scrubs

the image back and forth in the timeline, much like a DJ does with vinyl)

as Kirby projected images of fireworks onto star-shaped balloons spread

throughout the auditorium. The balloons, in turn, cast shadows onto the

projection screen in the front, on which a small rectangle of image was

also projected. Audience members were invited to take away the balloons

as they left the theater, and as they carried them away, viewers could

see the fireworks moving through the space. The piece concluded when the

balloon supply was exhausted, revealing that the audience had taken the

screens with them. Kirby's strategy transferred the expected duration

of the work from filmmaker to audience, and as spectators carried out

the balloon "screens," their bodies became part of the work.

These

works raise questions about the choice and arrangement of the gallery

space and the motivation for manipulating the time of the projection,

which determine the engaged dialogue between the projected image and its

recipient surface. This exchange is also among Lynn Marie Kirby's primary

concerns, apparent in her performance-based works such as Twilight's

Last Gleaming, part of the S.F. Cinematheque's 2002 retrospective

of her work held at the San Francisco Art Institute and Yerba Buena Center

for the Arts. Because she is interested in the dynamics of viewing, Kirby's

work is directed in part at deconstructing the theatrical space. This

piece commented on the contemporary political climate and the ways in

which artists have talked about national history in their work. Twilight

was visually driven by the shifting pacing of music such as a quick-tempo

John Philip Sousa march and Jimi Hendrix's Star Spangled Banner,

which "stretched out the gesture" (a reference to how she scrubs

the image back and forth in the timeline, much like a DJ does with vinyl)

as Kirby projected images of fireworks onto star-shaped balloons spread

throughout the auditorium. The balloons, in turn, cast shadows onto the

projection screen in the front, on which a small rectangle of image was

also projected. Audience members were invited to take away the balloons

as they left the theater, and as they carried them away, viewers could

see the fireworks moving through the space. The piece concluded when the

balloon supply was exhausted, revealing that the audience had taken the

screens with them. Kirby's strategy transferred the expected duration

of the work from filmmaker to audience, and as spectators carried out

the balloon "screens," their bodies became part of the work.

Such interest in the "logic of the materials" is also a central concern of Felipe Dulzaides, who views his installations as "constructions of meaning." In his Dialogue with a Foghorn, which was included in last year's Bay Area Now III at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, Dulzaides juxtaposed a projected video loop of someone riding a bicycle with a headlamp in circles on the roof of a building, with an actual bicycle embedded in a wood ramp, suggesting a situation with no exit. Embedded in the side of the ramp was a television monitor playing a continuous loop of the image of a flashlight pointed at the potential viewer, accompanied by the sound of a foghorn, which was "answered" by the light and sound coming from the bicycle video. A skateboard, which carried a slide projector, projected images of a skateboard navigating cracks while rolling down a sidewalk. The continuous loop of these elements set up a metaphor about endless repetitive situations, demonstrating Dulzaides's interest in observing such conditions through time.

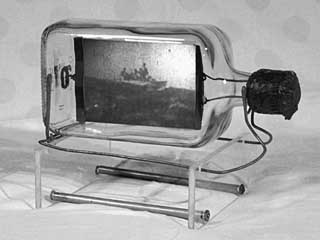

Thad Povey also takes this approach in his film projection work, apparent in his Ship in a Bottle series. With these works, Povey has played with the interface between the material and incorporeal, using looped images projected on tiny screens mounted inside various shapes and sizes of bottles, emulating the manner of ship-in-a-bottle hobbyists. For Wrapped Around the Screw, Povey directs a quartet of projected images at mirrors on the floor, which optically divide and reflect images of sailing ships back onto four tiny screens. Similarly, in Escape Velocity (formerly, Rocket Ship in a Bottle), the image of a spacecraft appears to take off inside the bottle. The emotional qualities of the work are heightened by the visibility of the film loop and the projector, the sound it makes, and the nostalgic quality of the film. While this nostalgia resonates on conceptual and emotional levels, these pieces also embody an inherent paradox as one considers sailing ships and rockets blasting off within the contained space of the bottle.

Povey's

series also raises questions of scale and its impact on perception, which

is integral to the concept and realization of the work. The collaborative

group silt—Keith Evans, Christian Farrell, and Jeff Warren—addresses this

question by slowing the pacing of their films to what they call "geological

time," creating a sense of vastness and a relationship between nature

and the body. Self-described "paranaturalists," the trio describe their

work as a "cinematic extension of the body and the earth," implying not

only boundless scale but also the vertical layering of time. These various

time references—biological and historical in addition to geological—simultaneously

situate the body as a small humble element and as a "vast" transforming

larger entity. The implication of geological time is also formal, as the

film surface is a microcosmic mineralogical environment that has landscape

properties in a state of flux and erosion.

Povey's

series also raises questions of scale and its impact on perception, which

is integral to the concept and realization of the work. The collaborative

group silt—Keith Evans, Christian Farrell, and Jeff Warren—addresses this

question by slowing the pacing of their films to what they call "geological

time," creating a sense of vastness and a relationship between nature

and the body. Self-described "paranaturalists," the trio describe their

work as a "cinematic extension of the body and the earth," implying not

only boundless scale but also the vertical layering of time. These various

time references—biological and historical in addition to geological—simultaneously

situate the body as a small humble element and as a "vast" transforming

larger entity. The implication of geological time is also formal, as the

film surface is a microcosmic mineralogical environment that has landscape

properties in a state of flux and erosion.

In a conversation with Keith Evans, he spoke of the group's interest in the primacy of sensation, which motivates them on occasion to include performance elements and sets up an emotional dynamic among the space, the filmmakers, and the viewer. In works such as biotriptych, part of the installation/performance All Pieces of a River Shore, the group's investigation of film emulsion and surface has the quality of a microscopic probing into the earth's layers. Unlike some of silt's work in which camera images and emulsion manipulation are combined, biotriptych does not include camera images. Instead, the film stock has been treated with various bacterial agents which have eaten patterns into the emulsion. The film's intrinsic qualities, its small gauge and wear through being processed and projected, further compound the breakdown. The material of the stratified levels, arranged to form unique compositions, is alternately diffused and judiciously focused with hands and tools during the performance projection, creating the experience of images dissolving and materializing. The remarkable light and the slowly shifting abstract imagery, created by the combination of these natural and manipulated processes, become a transcendent experience.

In his essay for the comprehensive catalogue that was produced for Bruce Conner's inspiring and illuminating exhibition 2000 BC: The Bruce Conner Story Part II, Peter Boswell creates an enchanting comparison between Conner's work and the wayang kulit, the traditional Indonesian shadow play. He explains how the audience can choose where to sit to experience this all-night epic. Some audience members prefer the side of the screen where they can witness the puppet master, expertly bringing his characters to life, observing and appreciating his skill with the mechanics of his art in tandem with the accompanying gamelan musicians. Alternatively, spectators can sit on the other side of the screen, willing to suspend belief and relinquish themselves to the magic of the candlelit shadow theater.

In this wonderfully allegorical way, Boswell proposes that both the material and transmutative perspectives from which Conner's art can be considered insist on the recognition that the experience of his work is perpetually mutable; and that the seeming alchemy with which Conner allies image or form with meaning implores the viewer continually to reconsider its essence from both sides of the screen. This idea epitomizes the intent and experience of projection art, suggesting its vast meaning and potential across physical, conceptual, media, and perceptual boundaries.

Terri Cohn is a San Francisco-based writer, curator, and art historian. She is a contributing editor to Artweek, and regularly writes for numerous other publications, including Sculpture, Art Papers, and Camerawork. She wrote a chapter about place-specific projects for Women Artists of the American West (McFarland & Co, 2003) and is working on another book.

This article was first published in the September 2003 issue of Release Print, the magazine of Film Arts Foundation. © 2003 Film Arts Foundation