Underground Film-Maker, Jon Moritsugu, Turns Rancid Meat Into Beggar's Banquet

by Jack Stevenson

A

lot of people sacrifice for art, but

not everyday does somebody get their

tongue stuck to a frozen Cadillac

hood ornament for it -- something

that almost happened to the female

Elvis impersonator in Jon Moritsugu's

first film, DER ELVIS. It wouldn't

be the last sacrifice an actor was

compelled to make for the Hawaiian-born

director, who, in a medium increasinly

characterized by slick technical polish,

has cranked out some of the most strikingly

primitive films that ever rattled

through a movie projector.

A

lot of people sacrifice for art, but

not everyday does somebody get their

tongue stuck to a frozen Cadillac

hood ornament for it -- something

that almost happened to the female

Elvis impersonator in Jon Moritsugu's

first film, DER ELVIS. It wouldn't

be the last sacrifice an actor was

compelled to make for the Hawaiian-born

director, who, in a medium increasinly

characterized by slick technical polish,

has cranked out some of the most strikingly

primitive films that ever rattled

through a movie projector.

The 23-minute DER ELVIS, made in 1987 as a thesis project by Moritsugu who was then enrolled in the Semiotics Department at Brown University, unspools at first glance as a sawed-off assault on The King at his most mythical and grotesque. Elvis fans who unwittingly attended screenings, as they did in Arhus, Denmark, were outraged. Yet it can be argued that the film is never actually mean-spirited since it never penetrates the layers of myth-making to take a slap at anything that ressembles a real person. Stuffed with a mix of multi-media regurgitation and live footage, it ressembles a cut-and-paste punk fanzine more than a movie, but it's a fitting approach to take with the twentieth century's most schizophrenic pop changeling.

In the spastic throes of a series of shocks, fits, and seizures, it expends the same tortured, bellicose energy at the audience that a bloated and sweaty Elvis expended on the business of living. The film slips and lunges about with the same blind fury that typified Presley's imaigned daily attempts to climb out of the bath tub. It seeks to depict the biology and velicty of his legendary top-heavy crash with grainy images of raw meat, a dead killer shark hoisted onto a dock, and food slopped onto a plate. In its sound and fury signifying nothing, it echoes the dying trumpet blast of a doomed cultural elephant thrashing about in the quicksand of its own media-created myth. The film, too, thrashes. And if it causes damage, it's mostly to itself.

As for insight into the director's working methods, the aforementioned hood-licking episode fairly accurately diagrams his approach to stanard film-making prcedures like obtaining permission for location shoots; Jon and said Elvis impersonator snuck into said Cadillac dealership in mid-winter without permission and filmed for two minutes before they were chased out and the cops were called.

Ironically we have the Kodak Corporation t thank or giving the world one of the most aggressive and caterwauling assaults ever foisted on a movie audience. After Moritsugu had almost completed filming, Kodak, in their corporate arrogance, discontinued their 16mm color reversal print stock without notifying a soul. It seemed DER ELVIS would never be made until Jon found a round-about way to print it - albeit with a sound loss.

"To compensate for this", Jon recalls, "I did a very aggressive experimental sound-mix - boost the treble, everything 'in the red' - by which the sound became a major character in the film."

SLEAZY RIDER, from 1988 - also 23 minutes - was a similarly irreverant toss-off of EASY RIDER. A wild road trip with two scurvy biker chicks predictably degenerates into violence and depravity with a weird fairy-tale twist. It was all shot without time, a crew, money or permission, mostly in abandoned buildings in the notoriously dangerous ghetto of South Providence, which Jon recalls kept things exciting.

The live footage in SLEAZY RIDER was, as in DER ELVIS, doped up with mixed-media flotsam and jetsam like grainy snatches of porn, video games, unreadable charts, comic effects, etc. And, like DER ELVIS, it was a battle against technical setbacks, primarily a shitty camera that ran at the wrong speed and threw the live sound, being recorded on a cassette deck, out of sync.

"It was in post production", says Jon, that I really had to experiment with the actual film medium to come up with a solution for putting together SLEAZY RIDER in an original and kick-ass way that would transcene the technical glitches and equipment failures".

There was another mechanical fuck-up in 1988 - Jon's right arm got caught and crushed in a conveyor belt at the shipping company where he worked. Extensive surgery and months of physical therapy restored use of his arm, and the settlement money restored his bank account and allowed him to plunge onward with his film-making. To this day the x-rays of his mangled right-arm sit in a back-lit glass case in his living room, in the same manner tha big Hollywood director might display an Oscar.

His next film, the awesomely primitive grunge-punk MY DEGENERATION (1989), about a female rock group that sells out to the meat industry, was originally slated for thirty minutes and stretched out with a practically 1-1 sooting ratio into a feature length seventy minutes. Again the live footage was leavened with all manner of experimental interludes from negative frames to emulsion scratching to model shots and crude animation. Except for getting your ankle chewed by a rat, this film remains the most low-tech experience you can have in a movie theater, ad while his two previous shorts were usually screened in galleries and bars, the feature length of MY DEGENERATION conditioned people to expect something close to a "real movie" and this made the final product all the more radical. While the film got some good reviews, others weren't prepared for such a thoroughly primitive movie-going experience and introduced him to his first rabidly negative press -- and it seems to have energized him. MY DEGENERATION remains in many ways his most radical and gutsiest film.

Moritsugu was a fan of the French New Wave and the immediacy of those films, but it was John Waters' damn-the-torpedoes gutbucket approach to movie-making that exerted the most obvious influence on his first three films, all ofwhich were stylistically very similar. They figure today as key contributions to punk cinema and led him, in the late eighties, to be lumped in with the NYC-based "Cinema of Transgression" who were showing their films in galleries, bars, and any underground dive big enough to set up a projector in. But he never fit in comfortably with the black leather crowd. The fact that he was a University student, and looks back positively on the experience, should be enough by itself to disqualify him from inclusion into this "movement".

MY DEGENERATION burlesqued the eighties punk scene with the same low-tech piss and vinegar that PINK FLAMINGOES burlesqued the trash-hippie scene, but it wasn't 1972 anymore and there was no midnight movie boom to give life to a feral child like this - although amazingly, it was selected that year for both the Sundance and Toronto Film Festivals - both bastions of mainstream status-quo film ideology. MY DEGENERATION will hang forever like a skeleton in their closets.

HIPPY

PORN was his next film, made in 1991

with Jacques Boyreau, a pal from Brown.

Both filmmakers were then in the process

of moving out to San Francisco where

the film would have its first shows.

HIPPY

PORN was his next film, made in 1991

with Jacques Boyreau, a pal from Brown.

Both filmmakers were then in the process

of moving out to San Francisco where

the film would have its first shows.

HIPPY PORN was a take-off on French New Wave classics like BREATHLESS, but instead of boho Parisian knockabouts, the film focuses in unrelenting cinema-verite fashion on the petty intrigues, angst, philosophizing and squabblings of a small circle of art school students. The film was a departure for Moritsugu who eschewed the mixed media effects this time and shared control of the material, and yet is clearly stamped with his fondness for the French New Wave and his conviction that teen life was as much about boredom and nothingness as it was about kicks. And while it succeeded uncannily at what it attempted, its exhausting length, willfully superficial subject matter, obonoxious male lead - whom even the filmmakers were ready to kill - and wholly misleading title all combined to jinx it with the public, although it did get relatively substantial exposure and distribution in France.

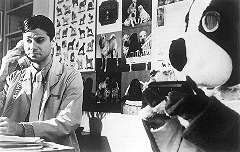

Right on the heels of his biggest flop, Moritsugu got his biggest break. In 1993, he was one of twenty independent film-makers offered 9000-USD by the Independent Television Service (ITVS) to submit a script for a series on "American TV Families" that they were preparing to produce and air. He could hardly decline.

His script, along with a submission by Todd Haynes, were among the seven chosen to be produced on budgets of 365,000 per film. He went directly from his minimum wage job as a record shop clerk to spending 80,000 the first week to set up his own corporation and get the machinery moving.

The

55-minute TERMINAL USA was the result

- a comically depraved family soap-opera

replete with traditional fifties suburban

sitcom dynamics but with superficialities

swapped for real problems,

and Caucasian characters for oriental.

ITVS wanted something ironic but not

necessarily extreme, and the selection

committee that had approved his script

freaked out when they saw the finished

film.

The

55-minute TERMINAL USA was the result

- a comically depraved family soap-opera

replete with traditional fifties suburban

sitcom dynamics but with superficialities

swapped for real problems,

and Caucasian characters for oriental.

ITVS wanted something ironic but not

necessarily extreme, and the selection

committee that had approved his script

freaked out when they saw the finished

film.

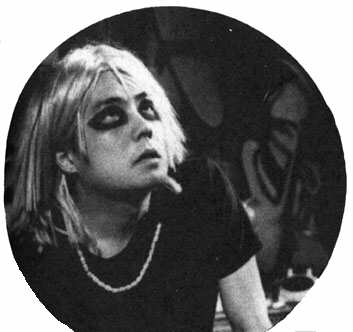

Many TV stations refused to broadcast it, but many of those who got to see it on air or later at a spat of festival screenings or on the European film club circuit proclaim it Moritsugu's masterpiece. It was clearly his most sophisticated, and accessible - if unavailable - piece of film-making to date. TERMINAL USA showed Moritsugu could use glossy production values to advantage, could spin a straight-forward narrative, and could act himself, portraying both "good son" Marvin and "bad son" Kazumi, in a classic twin role. His wife, Amy Davis, who has a lead role in every film scene, submitted an excellent deadpan performance as Eight-Ball, Kazumi's blase fashion-damaged girlfriend.

Critics raved too, almost in unison,

but the film didn't really help Moritsugu's

"career" and it shattered

his youthful idealism into the bargain,

souring him on any attempt to work

in "big time" film production

again. "I had a budget 25 times

larger than my previous projects but

sadly this didn't translate into a

film 25 times better", he recently

recalled - "it just meant 25

times more bullshit to deal with...

I was used to making films for 10,000

USD. I always thought it would be

a good and equal thing to work with

people I was paying, but it was a

terrible situation. I was boss over

fifty people, some of them were twenty

years younger than me, and I knew

they wanted to tell me to fuck off

but they wouldn't because they were

afraid to lose their jobs."

It also resulted in a fair amount of negative fallout from the Asian-American community who were unreceptive, in Jon's opinion, to anything but a standard Asian film about the struggles of their ancestors in a new land - the type of thing he found deathly dull. Considering the cocktail of incest, homosexuality, patricide, drug abuse, promiscuity, and violence he had served up, he might have foreseen their objections, but he appears genuinely surprised by attacks on what he considers a "Pro-Asian" and "forward looking" film. "You don't see Asian-Americans on TV. I see this as a first, a very Americanized Asian-American family... you never see that on TV which is really disconcerting... As usual, it freaked out the squares, but I did get a lot of support from cool Asians." In a bizarre turn of events, the film was almost selected by Northwest Airlines to show to passengers in flight - until a Northwest exec higher up the chain of decision-making nixed the idea. The fear was it wouldn't go down so well on flights to Asian countries (!).

Following

the unpleasant experience with the

film "Industry", Jon made

MOD FUCK EXPLOSION the next year almost

as an act of therapy. In another tale

of teen lust, boredom, and angst,

he indulged now familiar obsessions

for meat, high-speed, and exaggerated

gore via dream sequences and non-sequiturs

that entertained but tended to fracture

the narrative flow. Meat, in particular,

was a key obsession of his that had

figured prominently ever since DER

ELVIS, when he had wrapped up press

invitations to his very first screening

at NYC's The Gas Station in 1987 in

strips of raw bacon. "I think

meat is the perfect metaphor for our

post capitalist, commodified western

economic paradigm", he recently

responded to the inevitable query

about "what all the meat means"

- Plus it looks cool, feels neat,

and tastes great medium rare!"

Following

the unpleasant experience with the

film "Industry", Jon made

MOD FUCK EXPLOSION the next year almost

as an act of therapy. In another tale

of teen lust, boredom, and angst,

he indulged now familiar obsessions

for meat, high-speed, and exaggerated

gore via dream sequences and non-sequiturs

that entertained but tended to fracture

the narrative flow. Meat, in particular,

was a key obsession of his that had

figured prominently ever since DER

ELVIS, when he had wrapped up press

invitations to his very first screening

at NYC's The Gas Station in 1987 in

strips of raw bacon. "I think

meat is the perfect metaphor for our

post capitalist, commodified western

economic paradigm", he recently

responded to the inevitable query

about "what all the meat means"

- Plus it looks cool, feels neat,

and tastes great medium rare!"

MOD FUCK EXPLOSION had a polarizing effect on viewers. It won best feature-film at the New York Underground film festival, had hit runs in several American cities and today generally oudraws his other films, partly perhaps because of its great if misleading title. It has occasionally been programmed as a "Mod" film, on several occasions alongside QUADROPHENIA. When the film drew crowds of Mods at the Vancouver film festival, Jon took the mic: "Thank you all for coming, and to all you Mods out there, this film has absolutely nothing to do with you." A disgruntled Mod later wrote him a nasty letter threatening to track him down and drive his 64 Lambretta scooter up his ass if he ever set foot in Vancouver again. The Asian group that gave him a 500 USD grant for MOD FUCK EXPLOSION and expected some kind of "Asian Film" was no doubt also confused.

In Europe, it opened at the 1995 Berlin Film festival in a huge theater where the reception bordered on mass hysteria. This unveiling helped to spin off the film as a hit on the German film klub circuit, where it continues to draw. However a lot of people who like other Moritsugu films don't care for this one; some think it lacks the raw, retarded charm of his early films and that the convoluted structure and deadpan acting tends to undercut dramatic tension and make it aimless, which it seems fully intended to be.

Moritsugu's

most recent film, FAME WHORE, from

1997 is a three-part narrative on

the absuridities of fame culture in

America, and he drew on much of the

same local crew and acting talent

that he has used eve since his move

to San Francisco. Though replete with

some characteristic Moritsugu touches,

FAME WHORE stands as his most orthodoxly

structured feature film to date and

seemed the likeliest candidate to

cross-over into "above ground"

success. But it didn't, despite a

smash run in Los Angeles where it

garned good press and a five-week

holdover at a "legit" theater.

Moritsugu's

most recent film, FAME WHORE, from

1997 is a three-part narrative on

the absuridities of fame culture in

America, and he drew on much of the

same local crew and acting talent

that he has used eve since his move

to San Francisco. Though replete with

some characteristic Moritsugu touches,

FAME WHORE stands as his most orthodoxly

structured feature film to date and

seemed the likeliest candidate to

cross-over into "above ground"

success. But it didn't, despite a

smash run in Los Angeles where it

garned good press and a five-week

holdover at a "legit" theater.

Although very popular with some audiences, FAME WHORE didn't make the splash on the festival circuit that could have propelled it to wider exposure, and it did receive some poor reviews from critics who might have been expected to like it. For whatever reason, it didn't generate the expected buzz, and wasn't the breakthrough it could have been, considering its more accessible subject matter and structure and some truly excellent acting.

Jon believes this is due to the fact that the film is markedly different from his other work. "They want you to make the same fiilm over and over again ten times - I refuse to do this." While he could easily make a splash every year on the Underground festival circuit with yet another perverse, fucked-up, and provocative film, t must be getting a bit predictable for him. The trouble with FAME WHORE was, as an industry insider might put it, that it fell into the cracks between the Underground and Independent market segments and didn't connect solidly in a big way with either audience. But maybe that's because in the tightly controlled world of comercial film exhibition, where a lone self-distributor has no pull at all, it just didn't get the chance.

While Moritsugu has more than his

share of moxie about movie PR and

is willing to play the necessary games

to give his movies life, he still

stuffs his press kits full of the

bad as well as the good reviews, still

makes 16mm films and edits them by

hand on an "old-fashioned"

flatbed, and only recently broke down

and got a fax. And he still self-distributes

his films. Considering that many theaters

are phasing out their 16mm operations,

and those that still show 16mm sometimes

charge the film-maker 1000-USD just

to install a projector, it is tough

work. And he still finds it absurd

when people try to tell him he has

a "career"

Moritsugu has reached an interesting juncture today. Despite the fact he is still at heart - and still defines himself as - an underground film-maker whose work still exults in an unhinged low-budget joie de vivre, he appears "well-positioned" to cross-over and make an impact in the world of independent commercial feature films.

Today, armed with a completed script that he claims is ten times better than anything that he's ever done before, Moritsugu is easger to conquer new territory as he begins to put in place financing o the new film with the help of producer, Andrea Sperling, whose been on board since TERMINAL: USA.

Can this Christian survive in the den of 20-Million dollar lions unleased by the likes of Miramax and Fireline, who gobble up screen ad space? Could he ever stand to be caged in the same cocktail lounges as the scenesters, hipsters, and Industry types he finds so unpleasant?

Maybe he can do all that, and maybe someday he'll have a film playing down at your local megaplex, but it doesn't happen everyday. The last film-maker to pull himself up by his own bootstraps - rather than floating up on a cloud of puffed hype - was a guy named Waters.

Yet regardless of whether a break-through ever materializes, Moritsugu's achievements have thus far been significant and unique: He has demonstrated that commercial feature film-making can still display spirit and spontanaeity, and that "low-budget" can be a positive, not negative term - a term of liberation, not limitation.

At least he doesn't get chased out of Cadillac dealerships anymore. And if he ever hits "the big time", maybe he should send a residual check to that female Elvis impersonator who 13 years ago almost sacrificed her tongue for art ... or something.

THE END

(Jack Stevenson is a film writer, print collector and distributor living in Denmark since 1993. This year he has published books on drug and sex cinema (ADDICTED; THE MYTH & MENACE OF DRUGS IN FILM, by Creation Books, Uk, ISBN: 1840680237 and FLESHPOT: CINEMA'S SEXUAL MYTH MAKERS AND TABOO BREAKERS by critical Visions, UK, ISBN: 1900486121) and is currently working on a book about Lars von Trier.)