Dr. Yes and the Mystery of the Mission, Part Seven

9 Sep 2009

O Rose, thou art sick!

The invisible worm

That flies in the night,

In the howling storm,

Has found out thy bed

Of crimson joy:

And his dark secret love

Does thy life destroy.

--William Blake, "The Sick Rose"

Dark Hippy

It turned out that the FBI's COINTELPRO project under Nixon had infiltrated Dr. Yes's father's inner circle of hippies, yippies and activists. The Feds had not anticipated an unforeseen side effect of the strategy however, and this was that some of their agents had "gone native" and joined the Movement. Many a G-Man had done way too much LSD (in the interests of National Security) and had started seeing everything being connected and had forgotten all about J. Edgar Hoover, Washington and whatever else it was they were supposed to be doing.

Like the intrepid undercover cops who join the Mafia, many came back so changed by the cultural shifts required of them, that it was no longer a safe bet by their handlers that they were even remotely reliable.

By the same token, many on the underground were also strangely and unexpectedly fusing aspects of extreme conservatism into their world-view. For example women fared only slightly better in some underground networks than their sisters in the "straight world" and the counterculture was, for all its support for the Panthers, largely a white-middle-class-kid-sticking-it-to-the-man trip.

African-Americans, of course, had to deal with the system every day in every way and there was never a way to take a holiday from the misery, for them, of being an outsider. But a clean-cut white kid from the 'burbs could always call Mom if he needed to and take a holiday from the Rumspringa beat of the Haight, should the going get too intense. The Haight had once been a black neighborhood, until all these honky bitches had started fucking up small apartments by starting fires in the bathtubs, cramming the rooms with their shit and candles, and setting the fuckers on fire sometimes. Charred hippies made the foulest stench, and the burning/tripping ones falling from the second floor windows in the bigger traps fell to the floor like laundry. Yes had befriended an older black guy who had once owned an apartment building near Cole and Waller

"Rent out an apartment for one or two people, these outta-town hippy fuckers fill them wall-to-wall with freaks--like up to 20 or 30 at a time. Made a landlord's life a fuckin' misery!"

Racial discrimination, as practiced to this day in San Francisco, is usually a very subtle thing. You sometimes still see the signs, thought Yes, in shops, in bars: "We Reserve the Right to Refuse Service to Anyone." Even in the 60s, the newcomer of color who walked into a lunch counter in the Richmond, the Sunset, the Mission, or, with time, the Haight, was never sure whether he would get a bite to eat or a confrontation. All even more of an insult when, back during the war--only twenty-five years earlier--the Hunters Point shipyards had some of the best-paying jobs in town. A man could even own his own apartment building.

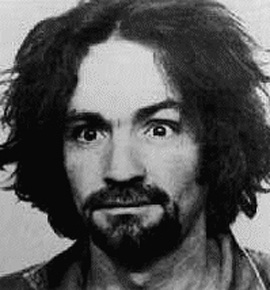

Then there were the real solid, unhinged, certifiable gringo head-cases like Manson, just a few blocks away. That murderous freak's take on the idea of the commune, the role of women, the music of the Beatles and interpretations of the "role of carnival" in general made the whole counterculture just have to face itself in the mirror. There, faced with the reality of what was sometimes really going on in the Haight, the hippy saw himself as he sometimes really was - the pretty Jesus as the hanged Judas and slaughtered innocents all as one. He had betrayed himself.

Mixed in with the flowers and the love and the peace and the bullshit and the cheesecloth and the incense was the sickening stench of death and of murder. If not of movie stars, then of ideals, of dreams and of What Was Really Possible. You did not have to be Nixon to condemn a hippy. The fuckers did it to themselves. Like Yes's father, the ultimate death-of-hippy motherfucker: sealed and cocooned like a Pharaoh of freaks. The King Tut of Trippers. Caligari's Somnambulistic Sleepwalking Suicide.

There was, at the end of the day, in terms of the shared sense of entitlement, self-interest and institutional vanity, surprisingly little to distinguish the COINTELPRO Federal undercover G-Man from the Hippy he was trying to emulate. Infiltration meant simply slightly modifying Washington's official brand of white male hubris for the 'unofficial' type promoted and enacted on Haight street. Each hippy was thus his own double-agent. We should thus not be surprised that so many became the despised yuppies whose ideology has now become for all intents and purposes the official one of today's western hemisphere (the baby boomer and his gen-x children, in terms of sheer numbers, won out in the end after all).

Rather we should be surprised that so many of them continued to convince themselves that their struggle had been for anything OTHER than what Debord had so accurately described as the Spectacle. The U.S. Space Race and the Cold War were perfectly embodied in the counterculture. Boldly going, in one way or another to the moon, to the Haight, to Vegas with Woolf in his white convertible--all were going. Going higher. Going. Everything Must Go.

Ginsberg, as good a poet as he was, was really was thus as Debord dismissed him, the "Mystical Cretin." And not even William Burroughs, Midwestern enough to cut through the thickest bullshit had a hide thick enough to remain untouched by the mystical, the occult, and the self-delusional. As Europe 2.0, the USA, had shed the most precious thing that Europe had going for it amidst its murderous self-annihilation--its sense of reason, rationality. Or order. Of anti-madness.

Then there was that whole division within the scene about "the role-of -technology-in-the-movement." Well wasn't LSD itself a technology? Wasn't Hendrix's amazing electric guitar a technology? (Of communication? Of transcendence?)

The Big Question: should these big-ass Stanford computers be used to liberate the people, or to reinforce the interests of control, profit and the war? I guess that little chestnut was still a hard one to crack, thought Dr. Yes as he flipped through a shoe-box filled with Polaroids of his father standing with pioneers of the computer movement. At the time they were working with artists to create multimedia light-show extravaganzas, early videogames, and computer- generated poetry, music and movies. There they were. Proud in their sta-prest shirts and ponytails and beards, next to the mainframes, posing as if they were dancers in a Broadway musical. There is no smugness like that of the system administrator high on his own control fantasy. Then or now, thought Dr. Yes. I'm thankful for what they produced. If only the smugness could be removed as easily as an Atari game cartridge.

As far as Yes was concerned the contemporary plethora of third-world-made-but first-world-enjoyed "iPods," "iPhones," "iMacs," had in making the computer and networks more available somehow also underscored and reinforced the interests of the worst players in the world. These iPeople should get some iPolitics and remember the iRevolution that got them started. The iPhone? Gimme a break!-- you needed to pay a minimum of $75 a month just to use the thing, then the device itself cost at least $400! Power to the people? All this from a company that got its start from selling blue box devices to make FREE PHONE CALLS!?!? Well at least Woz was still on side?

The liberal reformism of the Birkenstock-wearing, organic-food-eating, soy-latte-sipping software engineers in the Valley were, as he knew full well, in amazingly stark contrast to the deeply right-wing political beliefs of the ones who pulled the strings down there: the ones who really cut deals with Washington and generally had turned the whole past forty-five years of post-War digital experimental culture and handed it over wholesale to the torturers, the police, the military and the corporations. (Wasn't there that film by that German dude about all this? Dammbeck?)

As Yes pieced together the puzzle of his father's life, he could see the pattern emerge. And it went something like this:

His father had started a kind of free-for-all love-in multimedia workshop lab scene at the 992 Masonic houses sometime around 1966. All kinds of kids and freaks had gradually turned up and, like Coppolla's Zoetrope movie studio a few miles North-East on Folsom ("Utopia," as they had called it), had even enjoyed some success as a kind of hotbed of creative activity and alternative thinking. But the bigger it grew the less stable it became.

Pretty soon undesirables were ripping off cameras, blackboards, chairs, and video and film equipment and were generally exploiting the whole thing for their own ends. It was like the Beatle's Apple Store as satirically depicted in the film, The Rutles. Despite all this, things got done. Films were made, protests were held, flyers were published. Comics were drawn. Drugs were done. Sex was had. Food was given away. The Yellow Frame of the Diggers was placed around everything, like the one around the National Geographic magazine cover. The Diggers were fine, as long as their own sense of their own self-importance remained unchallenged. As progressive as they thought they were, behind every utopian activist was a drill instructor. The Vietnamese were winning because they were able to live with less, do more with less, turn the situation to their advantage. They had the moral high ground. They were winning. And much of what ailed them was not in any way contradicted by the counterculture, but rather echoed by it--in day-glo and in psychedelic colors. It was like the Partridge Family bus. You could paint it as if Mondrian had bombed it with minimalist lines and colors, but it was what it was. A prison bus. A school bus. A bus to nowhere. There was nothing ironic about the sign on the front of THAT bus either.

Then the Feds started sending their undercover stooges.

Except, one of them had befriended Dr. Yes's father. This was a guy who had shared the bed of his father. Someone who laughed as he cooked pasta with tomato sauce and basil leaves. Smiled as he had played guitar, sang and passed the joint. He was trusted. Loved. Cared for by the house to the point where many were willing to loan him hundreds of dollars, give him pot, and share a sexual partner. Anything. He made films; he joined the house on trips to Bolinas to go surfing and to enjoy massive sex orgies on the secluded beaches. Some were suspicious though. He never seemed concerned about busts. He never worried enough about the cops. He just did not gel on that one level that every freak, along with the cheap hoods and gangsters of the old-school, learned to develop: he was not hip enough to the heat.

Yes's gullible father trusted this guy so intimately that the shock of discovering that his closest friend was nothing more than a Washington flunky had led the guy to real suicide. But not just any suicide. No. An elaborate, symbolic art project--just like an Andy Warhol, Yoko Ono, Fluxus kind of deal: a body, sealed in a room, with a timed letter: "do not open until 2008," to his not-yet-born son!!! So a hippy had decided to have a child, top himself, and not be discovered until his own kid had outgrown him by twenty years before discovering his father's body. Man. It was enough to drive you crazy.

Keeping Up with The Commodore

And Dr. Yes felt himself going crazy. The cancer of lost ideals--the futility of good intentions that his father's life and death were shaping up as--was starting to affect his own mental health. It was as if the sixties had reached its lengthy corrupt arms of confused signals, that the Vietnam war had come back in the way the Weather Underground said it must: "home" to the American heartland. All of Ginsberg's Angel-Headed hipsters were filling their heads as one big angry fix.

One day Yes found himself pushing a Safeway cart down the street, mumbling to himself. For a while, no one could help him. He lost interest in the house, and only slept there maybe once a week. He went on wild journeys looking for discarded computer equipment. He would spend hours deciphering the data left on them for clues as to their previous owner's lives, as if the traces left by the detritus of the street was the answer to the morass morally he found himself in today. Could in some strange way, the accrued cultural refuse of a corrupt society, in being rummaged through and sorted, actually cleanse the soul of the finder? Could it possibly, amidst the avalanche of waste that America produced and left on its San Francisco sidewalks, in some way redeem the culture as a whole from its collective guilt? Guilt for fucking over the world? Guilt for starting pointless wars with defenseless nations whose only crime was representing an alternative way to live?

The cart grew heavy with discarded 486 computers running Windows 95. Pentium Threes running XP (but slowly). Early Powermac 7200s with 10 megs of RAM running OS 7.6 with a 500 meg hard drive. There was a brown plastic Commodore 64 (Dr. Yes remembered the Ad from Australia in 1978: "Are you keeping up with the Commodore, Cuz the Commodore is keeping up with you!"). And there was even a machine that a good friend of his back in Australia, a hacker dude called Diggler Davos, used to call a "Ned Kelly"--a Mac Classic (also applied to any of the early Macs that had the screen-in-the-case). It looked like Kelly in his improvised iron helmet, repelling cops with his six-gun.

Dr. Yes pushed his cart and slept at Golden Gate Park, staring up at the moon. Clouds covered it, then revealed it. He heard the seagulls circling above. He heard the distant fog horns of the bay. He pulled an old rug up to cover his aching head, and took a swig of Colt-45 before falling asleep.

He dreamed of his father holding him in his arms (an event that never happened), rocking him peacefully, stroking his hair. He had asked his father: "Father, what dreams have the dead? Do you think of the living? Do you feel our pain?" His father had said "We feel it all, but in seeing you suffer, we look forward to the day when you will join us that the pain we share might leave us?." Dr. Yes had looked back at his father and said "My problems, yours? Still thinking of number one, eh, Dad? You know what? I'm not sure I'm ready yet."

Dr. Yes will return in a forthcoming issue of OTHERZINE!

◊