The Ten List: 25 Years of American Experimental Cinema (1953–1978)

10 Feb 2013

Each of these avant-garde films is so complete in its inimitable cinematic reality that the scope of experience proffered collectively by them is beyond description. Made decades ago, they teem with new life as the context of their viewing continuously evolves: retaining their relevance and resonance. Fortunately, many of them have been preserved and restored in recent years by such entities as the National Film Preservation Foundation, Anthology Film Archives, UCLA Film & Television Archive, and the Museum of Modern Art. Prints are available for rental and purchase through such groups as Film-Makers’ Cooperative and MoMA Circulating Film Library in NYC and Canyon Cinema in San Francisco. In addition digital versions circulate online both officially and informally, and there are DVDs for purchase of collected works by several of the artists.

1. Rudy Burckhardt UNDER THE BROOKLYN BRIDGE (1953)

One sunny winter afternoon in 2004 when we were first getting together my partner and I went to PS1 for a Film-Makers’ Cooperative event hosted by Executive Director M.M. Serra. The special kids’ screening, curated out of the Coop’s holdings, featured 16mm films that in one way or another were imbued with the spirit of childhood. We all got to sprawl on low-slung seats and surrender to the marvelous play of and on the screen, and when Rudy Burckhardt’s UNDER THE BROOKLYN BRIDGE came around the image of the boys diving into the East River was so visceral that you felt the slap of contact, your head went under, the splash surrounded you, and you became weightless.

2. Shirley Clarke BRIDGES-GO-ROUND (1958)

It’s no wonder that Shirley Clarke entered filmmaking as a dancer: Her early work BRIDGES-GO-ROUND is fittingly an arabesque of mid-century New York City. Bridges and cityscapes follow a recursive, circular, looping, spinning form, the ride available to any passerby who takes note. First moving over water (nature: most likely the Hudson River), the camera then takes in the monumental engineering feat that is the George Washington Bridge (culture) and carries on from there. Clarke scales verticals, slides diagonals, and glides horizontals; colors cityscapes with gels in bright hues of the rainbow; superimposes and recombines parts to the whole; and plays her own film twice: first with a jazz soundtrack of music by Teo Macero and then with an electronic score by Louis & Bebe Barron—making this an ideal teaching tool on picture-sound relations, but more than that BRIDGES-GO-ROUND is an endless love affair, deservedly so.

3. Kenneth Anger SCORPIO RISING (1963)

The hurdle here is determining what exact title of the filmmaker to include: Is there an early Kenneth Anger work that does not cease to astound? The artist in person derides MTV and next generation(s) for failing to credit him—with his pairing of pop sound tracks and symbolically charged moving pictures—as a pioneer of the music video genre. This anchor figure of the international avant-garde remains more in the shadows than spotlight (for years living largely off royalties for his industry gossip book Hollywood Babylon), laying claim to the ongoing marginalization (or anti-commodity status) of experimental cinema. That said, I’m singling out SCORPIO RISING for its transgressive and arousing portrayal of an early ‘60s Brooklyn biker gang. Rife with fetish, fantasy, occultism, and even neofascism, SCORPIO RISING thrills in the sense of sneaking into forbidden territory; Anger’s queering of this masculinist subculture sets the stage for many acts to follow.

4. Barbara Rubin CHRISTMAS ON EARTH (1963)

Barbara Rubin’s CHRISTMAS ON EARTH is a psychedelic multi-sensory spectacle that would give any transport from Warhol’s Factory (of which Rubin was amongst) and the Exploding Plastic Inevitable further cause to celebrate. This radical film—the antithesis of inhibition and repression—stars men and women: a panoply of organs, orifices and erogenous zones, in sexual acts together, alone and in consort with the viewer. In the ‘80s I happened to be visiting Boston when CHRISTMAS ON EARTH was at MassArt Film Society...Rubin’s cinematic bodies materializing out of dark, empty, blank space an indelible memory.

Exhibited simultaneously as two 16mm picture tracks, CHRISTMAS ON EARTH requires two projectors configured so that the dual image merges into one (in a live superimposition), multiple performer- projectionists to hold variously colored gels before the two beams of original black-and-white images, and a deejay at the dials of an old school radio to turn from one to another station (music, news, talk, et al) and to linger on the cacophony of static and noise between. Later, I curated the film into the Body Hold Out Festival at WEBO Performance Space on the Lower East Side.

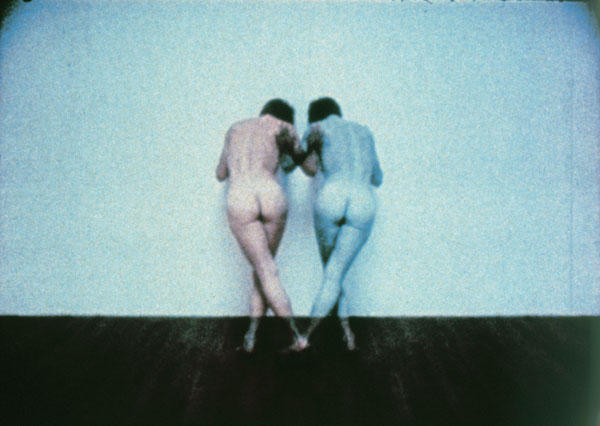

5. Carolee Schneemann FUSES (1967)

Carolee Schneemann’s FUSES, made with her then partner, the composer and musician James Tenney, situates the couple’s lovemaking—in all its carnality and spirituality—in the eyes of Kitch the cat. The artist cites her friend Stan Brakhage’s WINDOW WATER BABY MOVING (1959) and its focus on the reproductive function of his wife Jane Brakhage’s genitals (the film is a poetic document of their first child’s birth and is also shot in part by Jane) as an impetus: Schneemann wants to prioritize the vagina as a site of female eros, and succeeds to mount one form of pleasure atop another, central to which is an obsession with the material base of film’s representational capacity. Cinema is a medium by which Schneemann expands her practice as a painter, the touching, handling, disfiguring, and compiling of the frame(s) like the sex itself builds to a climax, if only to begin from scratch anew. I’ll never tire of viewing, experiencing, curating, teaching, and writing about FUSES, forever grateful for the space it invites me—and the world—to enter.

6. Tom Chomont OBLIVION (1969)

In 2009 I felt astonished and elated upon seeing OBLIVION by the now-late Tom Chomont for the first time at a Light Industry presentation by Saul Levine and Rebecca Meyers: Why had this 40-year-old experimental classic of inestimable cinematic, sexual and corporeal beauty eluded me for so long—especially in light of how the filmmaker and I were in the same early ‘90s NYC circle and I got to see him and his works regularly!? The shifts, reversals, layers, and repetitions of the untameable celluloid—black-and-white, negative, and color—result in absorbing rhythms and erotic rapture in perfect union with the subject: a young man masturbating, the camera positioned at the foot of the bed, hand gripping penis in the foreground, head with closed eyes in the distance, seen also smoking a Marlboro, sitting atop a kitchen stool, being part of the world visible to Chomont (who died in June 2010) that the filmmaker then illuminates for the rest of us. Filmmaker and curator Jim Hubbard has clarified for me that Chomont was able to achieve “those nodes and shadows” not through hand-processing nor optical-printing as I had suspected but rather by “shooting on reversal, then making a high-contrast, black-and-white negative of the section. He then A&B rolled it, offsetting the black-and-white negative a few frames.” Thanks to the Outfest Legacy Project for LGBT Film Preservation OBLIVION has renewed life, an existence to which we should all seek closer proximity.

7. Hollis Frampton (NOSTALGIA) HAPAX LEGOMENA I (1971)

Comprising balancing acts between photography and film, image and spoken word, concept and materiality, creation and destruction, thing and description, memory and presence, autobiography and myth, (NOSTALGIA) by Hollis Frampton destabilizes such relations as well as the very notion of “cinematic truth” through an appeal at once experiential and intellectual. First a photographer, Frampton culled from his archive an eclectic series including portraits of himself, Carl Andre, and Frank Stella, as well as one taken in Michael Snow’s studio—of which the voice-over narration explains, “If you look closely, you can see Michael Snow himself, on the left, by transmission, and my camera, on the right, by reflection.” What is actually visible, however, is not Snow’s studio but rather a picture of decomposing spaghetti. Frampton structures his film so that the verbal description of each image precedes that image, a picture-sound mismatch that despite becoming soon evident continues to jangle linear thought processes. The photographs are placed atop a hot plate, making them (their signification)—as they mutate into smoke and ashes—all the more cryptic while intoxicating. The voice discussing the photos belongs to Snow not Frampton, revealing the constructed reality of the diaristic “I” and heightening the sense of the uncanny.

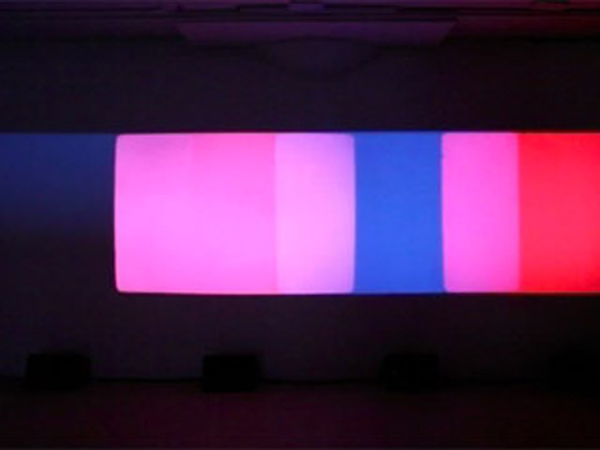

8. Paul Sharits SHUTTER INTERFACE (1975)

While the 2001 Whitney exhibition Into the Light: The Projected Image in American Art 1964–1977 was stunning overall, it was SHUTTER INTERFACE by Paul Sharits that absolutely riveted me. In 2009 I lucked upon the transcendent world of this multi-screen film installation a second time at Greene Naftali Gallery. Four 16mm loops comprised of ever-shifting monochromatic color fields (including black-and-white) are simultaneously projected to form one large horizontal frame (or rectangle or grid) of separate frames that by overlapping only partially both retain part of their original content and become something other based on what they happen to be combined with at the given moment. If the resulting minimalist frenzy fails to turn viewers into immediate addicts, then the cumulative sound—equally mechanical and insect-like—of four separate tracks may very well be the final repulsive seduction. At some point in my life I hope again to be in this space.

9. Bruce Conner CROSSROADS (1976)

In February 2009 I attended Bruce Conner’s Explosive Cinema: A Tribute at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. Dennis Hopper introduced the program of his late friend’s films, even citing Conner as the inspiration for his evocation of an acid trip gone awry in his own EASY RIDER. In such a context of Conner devotees it was exhilarating to re-experience already familiar works and even more so to witness others such as CROSSROADS in the first place. Conner appropriates documentation of Operation Crossroads, the government’s 1946 nuclear bomb tests at Bikini Atoll meant to gauge how naval ships would fare in such attacks—weapons experiments that were extensively recorded by both the military and the civilian press. CROSSROADS is a compendium of multiple aerial and surface views of the same two mushroom clouds over a ship-laden sea. Connor recasts the original footage in extreme slow-motion and sets it to Terry Riley’s hypnotic music, eliciting a sense of time opening up and inducing a meditative as opposed to analytical state. The formal beauty of the atomic blasts, intensified here by Conner’s intimate awareness of the medium of cinema, is immense. Ultimately, CROSSROADS feels more an elegy than a protest. Especially in light of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, CROSSROADS’ portrayal of Operation Crossroads suggests that we are not only implicated by the threat of our demise but that indeed we possess a compulsion for our own extinction.

10. Barbara Hammer DOUBLE STRENGTH (1978)

Having experienced DOUBLE STRENGTH by Barbara Hammer in widely varied contexts, I can attest to the reality that its vibrancy remains constant...befitting such an eternally current film artist. But I could not anticipate that when I brought Hammer to the upstate New York large public university where I once taught, the jock and frat boys would be so enamored of her—this living legend of lesbian experimental cinema. That they would choose her film about the growth and demise of her relationship with acrobat Terry Sendgraff as their favorite on the bill and write about their identification with the women was a teaching high for me. Aided by Hammer’s artistry (her mobile camera, her framing, her multiple imaging), Sendgraff swings through space boundlessly and spins out of and back into herself—a gesture that suggests the disillusion of the subject brought on by a merging with the other (such as in a love relationship) but is ultimately affirming of a comprehensive self-identity. DOUBLE STRENGTH shifts the ground under the viewer’s feet. It collapses distance between the myriad contagious motion depicted within and the supposed stable coordinates of the one looking from without. DOUBLE STRENGTH presents a dizzyingly electrifying experience.

◊

Caroline Koebel is an Austin-based writer and filmmaker. She has published in Jump Cut, Brooklyn Rail, Afterimage, ...might be good, Art Papers, Wide Angle, and elsewhere. Her experimental films and art videos have played internationally, with recent retrospectives at Festival Cine//B (Santiago, Chile) and Directors Lounge (Berlin, Germany). She holds a BA in Film Studies from UC Berkeley and an MFA in Visual Arts from UC San Diego, and is on faculty at Transart Institute (New York–Berlin).