Playfields, Mind Maps & Atemporality

10 Feb 2013

Note: “Playfields, Mind Maps, and Atemporality” will be published in Issue 2 of The Alpine Review. David Cox performs live for OTHER CINEMA’s Analog Church show on Saturday, April 13, 2013, and his latest video DO OTHERS screens on May 25, 2013, as part of OTHER CINEMA’s New Experimental Works program.

via booktwo.org

Associative diagrams, data, space, and play find common expression in user interface design, videogames, and urban planning in contemporary culture—all those floating 3D displays in movies, the gamification of mundane daily tasks, how stores look more and more like the touch screens that are replacing them.

Bruce Sterling talks of “Atemporality.” Atemporality is the feeling you get when you experience the old and the new forced into a singular moment. Like a 3D printout of an object designed in the 13th century. Or a Babbage difference engine made with the latest materials and computer-controlled design and manufacturing techniques. These are impossible objects in the truest sense that they stand outside time. Outside of history. They are a-temporal. It’s a feeling you get when you look to the West these days, particularly San Francisco, and particularly around the edges of that city. It’s in places like the Musée Méchanique where very early 20th-century coin-operated entertainment machines sit happily next to quite recent arcade computer-games.

The collapsing of old and new find expression in notions such as the Terrative. This neologism is the hybrid of territory and narrative and has emerged from the world of locative media. This is media that self-consciously and deliberately takes into account where the user is as it presents audiovisual and computer-generated content to them. Often locative media is combined with augmented reality. So place and story meet real and virtual. These collapsings are nothing new though, and the displacements felt by them would have been recognized by anyone around in 1901 to see the first aircraft take off. Or by those in 1916 who witnessed and took part in the first massacres by machine gun in the trenches of Ypres. Or who viewed the glow given off by radium.

Concepts of dynamism and kinesis characterized the 20th century. Power today is diffuse and ambient, rapid and static simultaneously. There are collapsings everywhere. All that is solid melts into air.

Žižek has argued that fundamentalists who respond with such venom to what they perceive as the excesses of today’s western liberal “democratic” society do so largely out of a sense of being excluded.

The silent and coded ways that cultural power builds force fields around itself is something that defies easy forms of computer visualization. Every upbeat TED talk with a breathless presenter performing some new PowerPoint illustrated technological miracle has a twin somewhere in the outskirts of a vast city in the third world, trying to sell a matchbox made from the recycled pieces of other matchboxes. Both perform miracles, at opposite ends of the global food chain. Homo-Sacer—the non-person would not exist were it not for the global trade in goods that just-in-time production has forced into being. There is no stranger or more perfect expression of contemporary Capital than a sign at mid-western Walmart checkout that shows a pictogram of three hands and next to it the words “fifteen items equals this many.”

Many contemporary films and videogames show scientists and specialists manipulating data in 3D as holographic fields of information. Floating, glowing holograms of the solar system, say as in PROMETHEUS. The terrains of Pandora in AVATAR, displayed for military and scientist alike. The head-up display is a product of the military fighter cockpit, and is installed in many recent model cars and passenger aircraft such as the Boeing 787. It combines the real world with information about that world simultaneously.

Augmented reality apps abound for the tsunami of Chinese-made touchscreen devices; sensor-studded, Wi-Fi enabled, the modern data user is attuned to her environment much like a pilot, or a sci-fi movie or game character. After thirty years of AR in pop culture, from ROBOCOP to TERMINATOR to HALO to the windows-within-windows of every GUI you ever used. It’s commonplace now to say that your games console can see you. Patents are fought over for who can profit from devices that identity if “too many” people are in the room to view a movie for the rental price. As Guy Debord once famously argued “The spectacle is not a collection of images, but a social relation among people mediated by images.” Today the spectacle sends sensor data into your living room and bills you for the privilege.

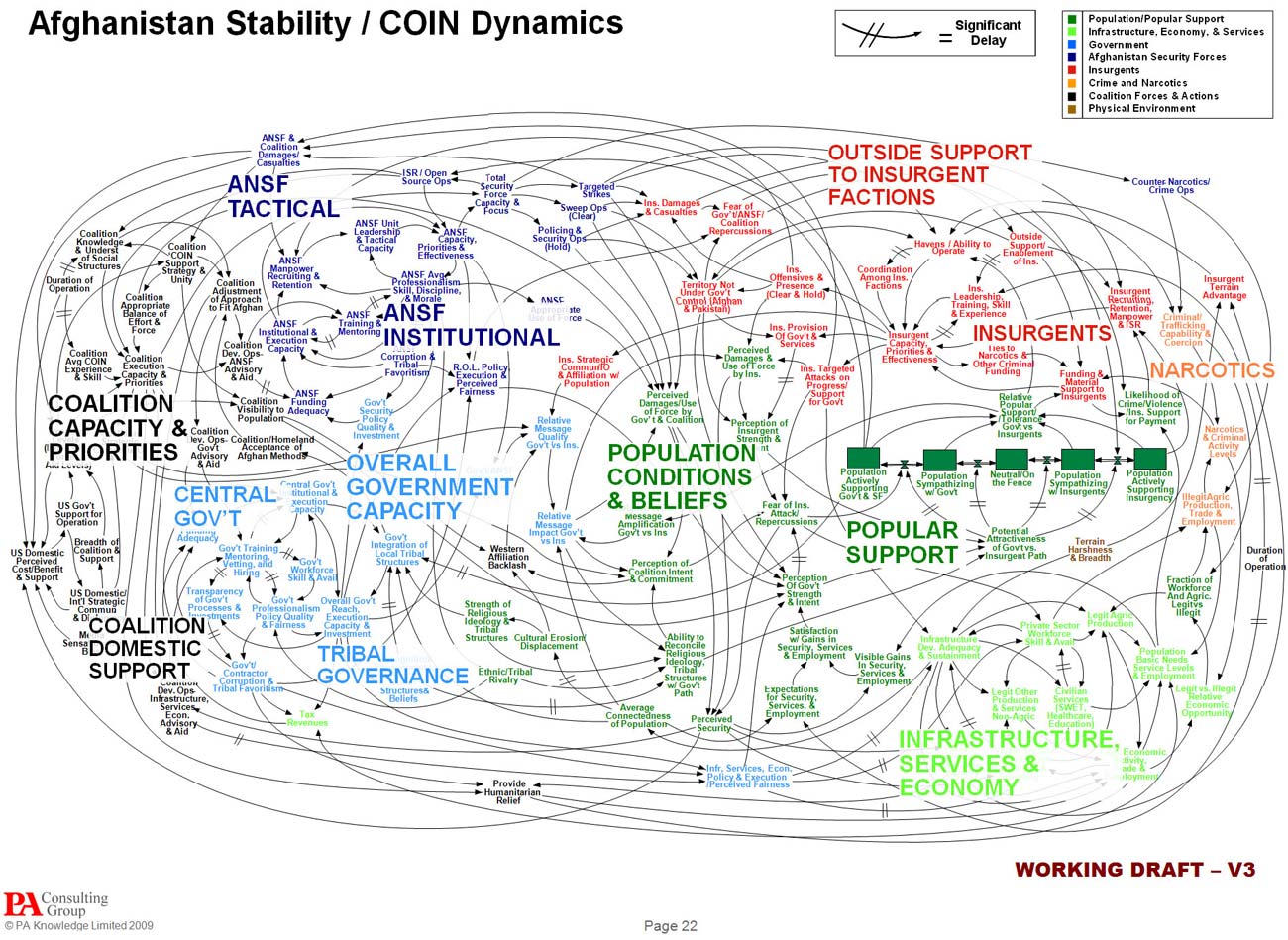

And when the information about the landscape becomes too dense or complex to fathom, often mind maps or flowcharts are prepared. Such as the famously spaghetti-like PowerPoint drafted by US Army supposedly to demonstrate the complex set of interrelationships between allied and local forces in Afghanistan. These rhizomatic arrays of ovoid text boxes connected by lines form a shape not unlike that drawn by the architect of the original Internet. When there were only three nodes to the network, it was simple to draw. Today, few computer programs could represent an entity whose complexity and scale defy most attempts to represent it.

In this cultural landscape of mind maps and playfields we walk. Like the pinball on the playfield of spectacular society we are bounced by the buffers of trade. Hurricanes and floods press us into the magnetic sinks thrown up by global warming. And we are thrown uncontrollably into the flippers at the bottom of the table by crushing debt and policies that seem contrived specifically to guarantee our exclusion from participation in the running of things.

“Your future dream is a shopping scheme” as the Sex Pistols once declared. Today Johnny Rotten is as likely to appear on a game show on UK television as anywhere, the shopping scheme, consuming and developing him along with his music and all else.

The first two world wars were expressions of industrialism run amok. From the cockpits of darkened wartime aircraft were guns fired, and at the same time, movie cameras recording the tracer bullets hitting their targets.

All participants in the world wars were dancing around each other in a frenzied dense fog of movement, dynamism, and kinesis. Within it all messages and data were sent, received, intercepted, encoded, and decoded. This massive dance of tangible and intangible, strategic and tactical, cultural and industrial power carried on into the post-war time.

Cybernetics proposed that the abstraction of perceptions that flowed from one agent within a battlefield to another formed a pattern, a kind of internal logic, irrespective of the outcome of any given conflict. Like the pinball in motion, or the tracer bullet filmed by its gun camera, all is in motion, and the motion is the message. Computers arise from the marriage of seeing and measuring ballistics. Understanding the velocity and range of ideas as well as ordnance.

The preoccupation with speed and motion in the Industrial Era resulted also in notions of modularity; the process of breaking things down into fragments and procedures. On the assembly line, Model T Fords and motion pictures both were handled by specialists who each attended to his or her field of expertise. Or else rendered ordinary people into robots of engineering, extensions of their machines.

This ironic conflation of real and unreal, dynamic and static is at the epicenter of our current kind of modernity.

All was about sequential motion, timing, breaking down events into individual chunks. Everything from machine guns and sewing machines to combustion engines, speed, motion, and standardized systems prevailed in the first half of the 20th century. Time itself was measured and broken and fragmented and divided. Spectacular society in the Cold War and the Space Race was a bitter struggle for time and resources. We were told that history would decide who could best manage vast populations with more efficiency.

The modernist preoccupation with movement and dynamism gave rise to the aesthetics of process. The theory of relativity reflected this new awareness and in mathematically and conceptually collapsing both time and space, set the stage for modernity’s post-WWII flight into space. The Space Race was nothing if not a colossal state-sponsored performance-art project, coupled with the logic of ballistics, with man as bullet and nation as ordinance. The moon, a likely target, seemed obvious in the 1960s. It’s up there, why not aim at it? Vietnam, much closer to home, though easier physically to get to for the USA, was much harder to actually claim for its own.

The increased clock speeds of computers in the ‘70s and ‘80s gave rise to chaos theory. Abstract forces hitherto hidden were laid bare by mathematical systems only ever faster computers could render visual. Chaos might be thought of as the postmodernism of science, the sampling of time, motion, and calculation for the purposes of fractal awareness. Chaos theory, like other cults of unknown, so popular in the 1980s, was in turn a result of the continued preoccupation with the measurement and control of space and time.

There is something so 1980s about the Mandlebrot set image, as it says more about the mid-1980s attempts to grasp the completeness of the universe and its rough edges. There is also something of the Cold War in those attempts to render nature within the aegis of CPU. Ancillary weaponry for both sides during the Cold War had always included the sonic, the cinematic, and the electronic. A new cartographic intelligence eventually joined all these; a mapping mindset of the data sphere where the process of code joined the deployment of better understood ways of enforcing meaning and ideology. Everyone was attempting to force time and space into ideological systems of management on a global scale.

In 1988 scientists really were prepared to be amazed by the patterns of the natural world that of course, were there all along. Computers merely proved the simplicity behind the complexity that for artists and for centuries was quite self-evident. Today, only a New Aesthete would marvel at the oddities thrown up by computers; not at their ability through math and graphics cards to echo the raggedy nature of a coastline, or the filigrees of a leaf or tree’s root-system, but by the unexpected glitches from within the computer system itself. Today the network, its sensors, and the ways these are connected are the natural coastline of our dreaming. Technology is nature.

via geographicalimaginations.com

Today our sensors see and feel for us. They place us well in relation to the data that we have made for ourselves and that which is made on our behalf by our proxies and intelligences. We might call this a kind of Intelligence faith. James Bridle and his ilk represent the naïve pastors of this cult of the ethereal. Every modernist time has its devotees, willing to find ghosts in their soup. Breton in the ‘20s, Leary in the ‘60s, Jobs in the ‘80s, and so on. The screaming madman at the core of Apple is of course his twin in China, ready to suicide at the Foxconn working conditions Apple management and iPad user alike are all too willing to ignore. Spoils the illusion, don’t you know. Think different.

For better or worse spambots and the other promiscuous data entities online that seek agency will take this reality as their own and will probably continue to do a good job of convincing us that they are not what they are. The existential problem for the spambot is a problem laid at our own feet. Am I a spambot?

Rampant sudden mass gun killings happen at random. The erasures on/within and around social media that surround them speak to the simultaneous effect of Facebook and Twitter and the like to strangely draw us closer and further away from such event-scenes.

The ease with which Bushmaster-style guns are bought, exchanged and modded, like toys or computers is one example of the modularity of networked violence. Gun tragedies are also mediated by a climate of dread, awe, and nihilistic indifference which also characterizes social media. This is true of remote violence in all its forms.

To what extent is a drone really a representative of US State Department policy when no one can be really sure who or what is controlling it? Who actually controls all the drones that are flying at any given time? It’s a chilling thought.

This ironic conflation of real and unreal, dynamic and static is at the epicenter of our current kind of modernity.

via What is an End of Stroke Switch?

Pinball machines are flat surfaces on which balls move that the player keeps in motion by way of flippers. The playfield is the area that pinball-machine designers call that flat surface. Most videogames have the equivalent of this playfield.

Urban design has long since taken its best ideas from the controlling impulse behind theme parks, with their dominant points of attraction (usually tall dominant structures distributed around the park), and paths to channel people to and from these nodal points. The management of time and space reaches no better apotheosis than at the Disney parks, where the science of extracting time and attention from people has reached a fine art. Gamifying the playfield of life is a neat extension of the theme-park pinball approach to city planning and urban development. Everywhere we go in contemporary cities involves passing through a nodal point of some kind where data is transferred.

Think of the symbol used in orthogonal 3D programs—it looks like a three-pointed 3D weathervane. Point your first finger forward, your thumb up, and your ring finger to the left. Here you have a right-handed approximation of the same symbol. The X, Y, and Z axes of the Euclidean space. A universe made up of primitives: spheres, cones, cubes, cylinders. Now this world is spread before us, and texture mapped and rendered in real time. It is festooned with colored overlays. And all the code that can be written is dancing behind it to make the physics happen. The skybox above shows a late afternoon. The long shadows, but a figment of the level-designer’s imagination. Those floating health and status bars above showing how much energy is left. They remind us, that our game world is much like the real one.

Level by level. Day by day we progress through the Spectacle. Our bank accounts, our encounters, our identities now are our mirror-image. Romance is like a game pickup, career events, so many power-ups. Gamified life in the spectacle puts us inside a permanent Disneyland, the ultimate frenzied pinball; where closing time never happens. The guards are watching. The obvious navigation points surround us, Matterhorns, Space Mountains. A figment of such structures twitches in and out of view on the horizon. It is an Augmented Reality view of the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center, an inevitable memorial to their memory, happening only on the anniversary of the event itself.

I turn off the AR. I look around at a city-wide ocean of black turned-off LCD screens. I try my hardest to remember to how to forget.

◊

David Cox is a writer and teacher based in San Francisco. His films include PUPPENHEAD, OTHERZONE, and TATLIN. His books include Sign Wars: the Culture Jammers Strike Back, published via LedaTape.