The Future is Back

19 Feb 2010

'Those who do not learn from

the future are condemned to repeat it' - Destroy All Monsters

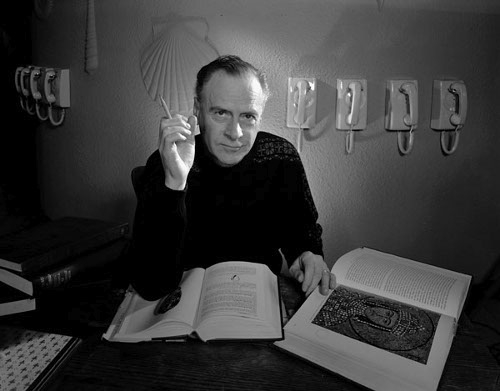

In January 1996, Wired magazine published an extensive interview with the celebrated author of Understanding Media, Marshall McLuhan, in which he discussed with great animation and insight the effects that the new digital technologies were having upon our most basic perceptions. In fact, McLuhan seemed remarkably alert and well informed for someone who had been dead for the past fifteen years. As citizens of the 21st century, we have naturally grown accustomed to such intrusions. It was McLuhan himself, after all, who had observed that we only catch glimpses of the future through the rear-view mirror as we reverse boldly into tomorrow. So where was this new voice coming from? Did it emanate from the past or the future? Or had our perceptions of progress and its discontents become so compacted that the future had finally become the rear-view mirror? And was it still possible to change gears with a phantom hand on the wheel?

At the actual hour of his death on December 31st 1980, the man responsible for introducing into mass consciousness such flashcard concepts as 'the global village' and 'the medium is the message' had been all but forgotten. There was a time in the 1960s, however, when Professor Marshall McLuhan's face would have been on the cover of Newsweek, his name slapped across car bumper stickers, his reputation as a wild predictor of cultural upheaval the subject of New Yorker cartoons. An academic who preferred talking with businessmen to his fellow academics, a soberly attired polymath whose perceptions meshed with the colourful sloganeering of youth culture, what plugged McLuhan straight into the rapidly overheating world of the 1960s was his ability to explain television to itself.

In an age when electronic telecommunication systems were still considered as primary conduits to the future, this was no small talent. The fact that such explanations were rarely understood didn't seem to matter much. 'Marshall McLuhan, what yuh doin'?' Henry Gibson would inquire with deadpan naivety on primetime TV as the media guru approached the height of his media fame.

When it comes to the future, however, you can't kid a kidder.

McLuhan's celebrity status was always directly dependent upon the degree to which he was systematically misunderstood, especially by the media. 'I have no theories whatever about anything,' he wrote to a detractor. 'I make observations by way of discovering contours, lines of force and pressures. I satirize at all times, and my hyperboles are as nothing compared to the events to which they refer.'

Ultimately an exercise in repetition, prediction works well on TV, organizing words and concepts into rhythms. All of human history is composed of reruns. In 1968 McLuhan had to be constantly nudged awake during a special advance screening of Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. 'It's nice to have the avant-garde behind you,' he observed afterwards.

When it comes to the future, expectations change.

Back in the 1950s, when McLuhan was first formulating his ideas on the media, the future was written about, discussed and analysed with such confidence that it took on an almost tangible presence, especially in the United States, where an unprecedented economic boom, coupled with a growing sense of its own importance on the international stage, prompted Henry R. Luce, founding father of Time Life Inc, to speak with increasing vigour of an 'American Century'. 'Why should we make a five-year plan,' the Partisan Review was wondering aloud by mid-decade, 'when God seems to have had a thousand-year plan ready-made for us?'

How many consumer goods and technological innovations were summed up in that word, 'ready-made'? How many indicators of prosperity and aids to gracious living? The future was no longer some vague and distant prospect. It was happening right in front of people's eyes. 'Progress is our most important product,' future president Ronald Reagan announced in a black-and-white television pitch for General Electric as the company's profits reached an all-time high. 'If you're sitting back at General Electric, you're probably falling behind.'

McLuhan was less concerned with understanding the future than in anticipating it. To define media in terms of their content was to ignore their influence upon the human environment, their agency as means of perception. With content scrambling at us from interactive videogames, live videophone transmissions via satellite from Baghdad, globally networked stock markets feeding back into themselves, this is a good time to consider the applications of a simple observation from McLuhan's Understanding Media, published in 1964:

'The electric light escapes attention as a communication medium just because it has no 'content'. And this makes it an invaluable instance of how people fail to study media at all.'

When it comes to the future, sincerity becomes a new form of irony. The advent of 'reality television' has seen to that. Meanwhile the light bulb has entered the toolbar of modern consciousness as an icon for creative thought - the 'idea' that flashes on over our heads, or at the top of our screens, alerting us to the arrival of something new and unforeseen. Or to put it another way, how many media analysts does it take to screw in a light bulb? Don't wait too long for an answer.

Deception is the new discourse. Electric light only offers a convincing illusion of daylight, its 'content' being all the activities that are now permitted to take place after dark. As such it represents a complex simulation of experience that passes virtually unnoticed at a time when digital technology is in the process of rendering itself invisible. Hardware and software are converging to the point of total dematerialization. The old configurations of data streaming will eventually vanish into one another, leaving the replication of sound and vision as the sole industry standard for communication. Information ceases to be an intelligible part of the environment, but functions as an element instead: boundless, formless, creating vast artificial ecosystems out of networked systems.

Like earth, air, fire and water, data will become a constituent part of physical reality, demanding an equally high degree of creative interaction. It is worth recalling at this stage that in 1936 McLuhan was at Cambridge University, pursuing postgraduate studies into how poetry 'remains intelligible so long as we separate words from their meanings and treat them as mere signs fitted into a sensory pattern' at the same time as Alan Turing was publishing the theoretical model of a machine that would constitute the basis of all future computing. Fiction has always been concerned with the precise assemblage of details. Turing's Universal Machine only existed on paper as a list of instructions, yet it was capable of simulating the behaviour of any other data-processing machine, up to and including itself. The model's sensory patterning of ones and zeroes, deployed on a tape of infinite length, unwittingly established Alan Turing as one of the great novelists of the 20th century.

When it comes to the future, some things only make sense in retrospect. There have always been ghosts in the system. McLuhan's 1996 interview with Wired took place by email, following a series of anonymous postings routed onto a popular US mailing site. Who was answering the questions remains a mystery: if the poster was not McLuhan himself, the magazine concluded, then it must have been 'a bot programmed with an eerie command of McLuhan's life and inimitable perspective'.

In this, the least anonymous of ages, personal identity is a destination: an email address, a function key on a mobile phone. A form of free-market reality, defined by the terminals accessible in our immediate environment, has come into being. Meanwhile, as McLuhan's collected works are repackaged for a new generation of readers, together with two biographies and a new series of collected unpublished lectures and papers, the revelation that McLuhan never actually wrote all of his own books should hardly come as a surprise. Authenticity is no longer an issue.

When it comes to the future, theories don't allow for much reaction time. Confronted with an unimpeded flow of data travelling at the speed of light down an endless network of fibre optic cables, they can only slow you up. McLuhan's inimitable perspective is precisely what's required now. Creativity requires confidence, a willingness not to understand, and both are lost in an instant. Just like switching off a light.

Back in the 1960s, things were

moving too fast for anyone to pay much attention to what McLuhan was

actually saying. To understand McLuhan was inevitably to misinterpret

him. Never to have read him was to have studied him well. TV, magazines

and advertising took care of the rest. The difference between then and

now is what separates notions of progress from those of anticipation.

The future should not be defined by what it will bring but how it displaces

objects, functions and institutions in time. Just as fiction takes place

in an artificially distended present, so creative thought anticipates

an endless future. Thanks to McLuhan, the future itself is revealed

as a means of perception, a 'communication medium' as powerful and

creative as any other on the planet. Like a phantom voice coming in

over the wire, the future is back. And this time it's personal.

National Endowment for Science Technology and the Arts.

See also: Ken's blog.