Jimm Juback:

Dada Bantamweight Rascal of 1970s Super-8

12 Sep 2012

There exists a letter-sized antiwar flyer from April, 1971, printed on an offset press and featuring a fist drawn by sophomore Link Yaco, which calls Ann Arbor Pioneer High School students to gather and march about a mile to the “Get Out of Vietnam” rally on the University of Michigan campus. The text of the flyer details “then we will return to school to see the Bison Boys’ production DANIEL BOONE in the Little Theater.” It should have read Bison Productions; the Bison Boys were merely the acoustic music trio and art-gang that consisted of Jimm Juback, Gary Malvin and Mike Mosher, a band assembled while working on co-director Jimm Juback and Tony LaRocca’s Super-8mm movie project DANIEL BOONE the summer before. After their first practice had been scheduled, Malvin told a girl who invited him to a party that his new group would gladly play there. The band’s mix of song genres, university-town wit and eclectic cultural allusions were characteristic of their filmmaking too, especially that of the effusive and jovial Juback. Viewed today, his 48-minute slapstick comedy DANIEL BOONE depicted Euro- and Native-American relations as crudely and stereotypically as the 1960s sitcom F Troop did. Yet with this April 1971 debut—to an audience containing many teens fired-up from demonstrating their progressive political commitment that day—sixteen-year old junior Jimm Juback established himself as a formidable, fun Super-8mm filmmaker among his teenage smart-kid peers.

Some of [Juback’s] films evince a dry and sophisticated (or stoner-Dada) humor, some set up absurd mise en scène...and some had surprise endings worthy of storyteller O. Henry.

Armed with his Kodak Instamatic M-14 Super-8mm movie camera, Juback went on produce numerous short films with his crew of friends, which included me. Some of the films evince a dry and sophisticated (or stoner-Dada) humor, some set up the absurd mise en scène that was characteristic of DR. CHICAGO films by Ann Arbor Film Festival founder George Manupelli, and some had surprise endings worthy of storyteller O. Henry. Though Pioneer High curriculum boasted a single Film Studies class, taught during the years 1971–74 by Bill Silverman, Alan Schreiber and Gwen Lagoe, respectively, it is unclear if Juback ever took it. He read Arthur Knight’s book The Liveliest Art (1957), supplemented with avid attendance at the annual Ann Arbor Film Festival (and its short-lived Super-8 Festival), plus a lot of movies shown free or for minimal admission fee on the University of Michigan campus. Juback was attentive to Dadaist film, the cavorting of artists in Rene Clair’s 1924 ENTR’ACTE or Hans Richter’s 1927 GHOSTS BEFORE BREAKFAST. Silent films were important, for that’s all that could really be produced with a low-end Kodak Instamatic Super-8mm camera his parents had bought him.

In the summer of 1971 Juback collaborated with Steve Dunning, who had just graduated from Huron High School, across town, on TIM OF ATHENS—which had nothing to do with William Shakespeare’s Timon of Athens, except to now give the protagonist an American boy’s name. Dunning, son of a poet teaching in the UM English Department, had a wry sense of humor and sharp intelligence. Witty and with a minimal capacity to countenance bullshit, Dunning could cut to the chase, to simplify an idea, a quality that served him well in his adult career in programming.

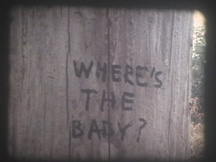

Juback told his idea for a film they could make in a weekend to Dunning. Opening scene, a baby doll is hidden by a nerdy guy in the bushes beside a rural road. There follow shots of the doll being hurled from a parking structure, floating in the Huron River, glimpsed in a car on the freeway, in locales around campus, etc. Then the guy would return, seeking the baby, and ask a passerby its whereabouts. “The baby’s gone” he replies. The End. Dunning replied “Ehh, sounds like a lot of work.” How about: The baby is hidden, title card “Around the block, five minutes later,” next the guy looks for it, “Where’s the baby?” “The baby’s gone.” Deadpan, stoned and Dada humor, and a movie no longer than need be.

One notes the trope of the missing baby in the song “Mother’s Lament,” an old music-hall ballad added by the band Cream, at the last minute, to their second album Disraeli Gears, likely in both filmmakers’ collections.

My own name appears first in the credits of THE GUY FROM ANOTHER PLANET, but that’s only because Fall 1971 I was enrolled in Mrs. (Gwendolyn) Lagoe’s Pioneer High Film Studies class, and wanted to submit Bison Productions’ late summer project for credit. It is Juback’s movie in premise—“A guy comes down to earth in an airplane, then goes back” —and style; he acts in its opening scene, and the film used his Kodak Instamatic Super-8mm camera.

Boys are playing tackle baseball in a yard, as a leather-jacketed intellectual in a chaise-lounge, played by Juback, looks up to utter (title cards) “Science can not explain everything that happens...as these boys are about to learn!” Gary Malvin, on the ground, points to something in the sky—an airplane! —and the other two do as well.

Warning their neighbor (their friend Tony LaRocca’s mom), she gathers her young children under her greatcoat like a bird would under her wings.

The boys rush to the airport to meet the plane, from which an alien emerges. He is given a drug, which he takes, and an ear of corn, which he bites but finds unappealing. He shows a map of the known universe, and where he’s from: off the map.

He gets back into the plane, all wave goodbye, and the alien departs. It was my own luck that I had been cameraman for the opening baseball and spread-the-alarm scenes, so not having been onscreen, I was chosen to play the alien. There are similarities, in the trope of interplanetary travel by airplane, to Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince, read in Mrs. Harrell’s 10th-grade French class the year before, though Juback hadn’t taken French.

THE FAMILY THAT ATE THE DINNER OF DOOM was filmed in Spring, 1972, starring Ray Curtin and his family.

Curtin, who lived across the street from me and my parents, was a graduate student in the UM Library Science Department, and had the Bison Boys play for the grad student party he hosted.

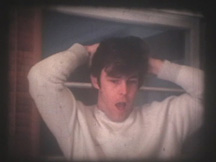

Like Tim of Athens, this film had a sotto-voce joke setup and punch line. Curtin grasps the sides of his head, gets a goggle-eyed expression on his face quite similar to Moe Howard of the Three Stooges after a bowling ball has bounced off his noggin, and mouths “I’ve got amnesia!”

Title card: “I have amnesia.”

He gets up from the table and runs outdoors. As Curtin spins in his front yard (hand-held camera jiggling with laughter), his children and dog run out too. Title card “Me too, daddy.”

Juback recalls:

COL. JEFFREY ABD-GAZA AND HIS BOY-GIRL WAR was made with Juback’s collaborator in film, comics and music, Link Yaco. There was a supposed enmity between those two, for Yaco had been, on occasion, a victim of Juback’s impish pranks. Yet in spring of 1972, Yaco had asked Juback to draw a comic for an issue he was editing of The Graphic Story Journal, the publication of a Pioneer High school club formed to get free access of school’s Ditto fluid-copy machines. Juback assented, but only if Yaco would help him make a movie.

In our films, even credibility was not an issue. The stiffer the actor, the better. What’s so bad about self-consciousness? We always layered the silliness—the plot AND its execution.—Jimm Juback

Yaco both filmed and drew intertitles for COL. JEFFREY ABD-GAZA AND HIS BOY-GIRL WAR. In an old band uniform, with a bogus saber-dueling scar across his face, Juback marches on to the Pioneer field, exhorting a boys’ gym class to join his army, to fight the women who are stealing their oil wells! “Abd-Gaza’s poorly trained troops rebel” reads the title card before the gym class members spontaneously toss Juback into the muddy, shallow pond beside the playing field.

An unfinished film, THE DAY IT RAINED (1972) was a summer afternoon project of Juback, Link Yaco, Alan Good, and Mike Mosher. Juback plays a shambling drunk in Burns Park, pathetically trying to refill his empty wine bottle with rainwater. Two pre-teen boys (somebody’s little brother and his friend) pose as Sears catalog models.

Juback recalls:

Some of the existing footage ended up in my own 1983 enlarged version of THE GAMBLING DEBT (PAID) (1972), shown at San Francisco’s Artists’ Television Access in 1996.

In WHAT GOES UP (MUST COME DOWN), filmed in the late Fall of 1972, Chris Tons played a lovelorn fellow who commits suicide by having an electric garage door decapitate him, or at least—we viewers are spared bloody details—crush his windpipe.

The movie’s sure-fire laugh is earlier, just after the hero has received the letter telling him of the loss of his girlfriend’s love. When we see the photo of the despondent, jilted lover’s girlfriend “Pattiy” (as she signed her farewell letter): it’s Jessica Juback, the filmmaker’s youngest sister, a toddler, not even in elementary school.

Juback reflects:

A-HUNTING WE WILL GO (filmed early Spring of 1973) starred Paul Remley as Bob Bailey, Private Eye. Extremely thin, with very long blond hair, Remley appeared in a choir in Juback and LaRocca’s 1971 DANIEL BOONE, and in films by Destroy All Monsters filmmaker Cary Loren in the mid-1970s too. Tim Johnson and David Cappeart played hunters, who get caught up in the movie’s O. Henry-qua-stoned-humor surprise groaner ending.

In Fall of 1973, Juback drove to Mexico City with a ride found on the Michigan Union’s bulletin board, and then proceeded to Ecuador. Taking his camera, several minutes of footage was shot by an Ecuadorean to later be shown in Michigan by Juback, usually accompanied by an LP of rondador music purchased there. As he strums guitar amongst indigenous Ecuadorean musicians, which he called “Jimmy and the Inca Spots,” an Incan woman remains motionless with a pitcher in her hand at an angle, as if unsure exactly what kind of camera, still or motion picture, she stands before.

In our hands the story itself was often subversive, and certainly many of the casting situations supported this.—Jimm Juback

KUNG FU KID (1975) features raven-haired teen beauty Francesca Palazzola (daughter of the UM College of Art and Design Dean Guy Palazzola, who had a how-to-paint show produced by UM Television every Sunday afternoon on WJR-TV, Detroit) as Patty Hearst. From unseen Symbionese Liberation Army kidnappers, Patty is rescued by a martial arts virtuoso played by Francesca’s 12-year old brother, Guy Jr. Juback inexplicably gave away the sole copy of the film in the 1980s to Francesca’s mother, yet remembers its:

A year later Juback began a film project with Ingrid Good, sister of Tim of Athens actor Alan, but it was never finished. Both Francesca Palazzola and Ingrid Good also acted in Super-8mm films by Cary Loren, who moved to Ann Arbor in 1974, and were photographed by him; Loren’s 1970s photos of them were exhibited in 2011 in Boston and Los Angeles.

Like Orson Welles, Woody Allen and Samuel Fuller, Juback appeared as an actor in movies that he did not direct. ARTHUR CRAVEN: DADA BANTAMWEIGHT RASCAL by Mark McNally, also shot for credit in Mrs. Lagoe’s Film class, starred Juback as the adventurous rogue at the fringes of Paris Dada. In 1976 Juback appeared in a movie by Rick Greenwald, sometime Destroy All Monsters collaborator, set to Patti Smith’s Horses, as Johnny, the boy “smashing his head against the locker.”

A movie by his peers consciously influenced by Juback’s style was BIG GLOBLE [sic] DOIN’S (1974) by Paul Adelson, Alan Lunk, and myself. An ant colony challenges the nation of Sweden to a space race, the Swedish astronaut climbs into the capsule (the trunk of a ‘71 Buick Special), an Estes model rocket blasts off and the ants curse their loss. Any intertitles are purposely misspelled or obscure.

Juback also worked in video, for Ann Arbor’s Public Access facility was active and welcoming, and would loan out Sony Portapaks to producers after a single training session. Juback conceived of POKER GAME, a game show held in early Fall, 1974 in the basement of Joint House Co-Op, a few blocks from the UM campus. Then that December, Juback dreamed up EDDIE’S CHRISTMAS, a holiday special about a garbage man asked by the Mayor to impersonate Santa Claus for his children. David Cappeart from A-HUNTING WE WILL GO was asked to play one of the garbage men, and did; his father Leroy Cappeart was asked to play the Mayor, but declined due to his very real Ann Arbor Mayoral ambitions. Whereabouts of these tapes are unknown.

Upon watching Juback’s movies about four decades later, what strikes the viewer is the inspired “tossed-off” quality...as well as the lack of completion. They don’t have soundtracks. The jovial, self-described “Slav so fine” thought of them as performances, something he would bring to a party or event and then comment upon during the screening, saying “Trick photography!” during any particularly jarring cut.

In the following decade, the age of MTV, Juback made some music videos. “Bison Eat Grass” and “La Bamba” (both 1985) made use of Super-8 footage, transferred to video with music added. Then living in Venice, California, Jimm Juback’s wife Joyce Lieberman shot Juback and me waving guitars in front of the Golden Gate Park bison herd on their trip to San Francisco, and their Venice neighbors dancing in the kitchen at a party. Recordings of Juback singing the Bison Boys’ 1970 song “Bison Eat Grass,” and Ritchie Valens’ “La Bamba,” were then employed as soundtracks to the VHS tapes.

As he was in the Bison Boys (1970–73), Juback was a prolific songwriter throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s. An Ann Arbor Observer story on the Zal Gaz Grotto inspired “Da Shrine Comedy” (1987), an orientalist tale of Masonic hijinks, where a fez was honored as an “admittance lid,” in a prominent Ann Arbor lodge he had often passed and wondered about. A music video was created when images were stop-action animated—in the manner of Terry Gilliam’s memorable Monty Python’s Flying Circus sequences—by Paul Binkley, a co-worker at the Chiat Day ad agency where Juback was employed, and continues to work as a junior account executive. Tim Sassoon, owner of a company providing film titles for IMAX films and others, shot a performance video of Juback’s band (all ad agency staff) Bourbon Warehouse Inferno, and also commenced a video of Juback’s song “Patio Furniture” that was never finished.

Is Juback’s form of funny little films an anachronism? A former student of mine recently sent me the link to a video shot in Super-8mm on YouTube called SKATE WITCHES. Produced by Danny Plotnick, then on the staff of the UM humor magazine the Gargoyle, it has the same sort of humor as WHAT GOES UP (MUST COME DOWN): Punk girls knock boys on the UM Diag off their skateboards, which they then steal. One wonders if, filmed in 1986, it was the last Super-8mm funny film shot in Michigan. Plotnick went on to produce wry films in northern California.

Upon watching Juback’s movies about four decades later, what strikes the viewer is the inspired “tossed-off” quality...as well as the lack of completion. They don’t have soundtracks. The jovial, self-described “Slav so fine” thought of them as performances, something he would bring to a party or event and then comment upon during the screening, saying “Trick photography!” during any particularly jarring cut. He was pleased to discover the historic “film explainer” tradition (called benshi in Japan) of a hundred years ago, the raconteur at the side of the screen. He may have seen that as his role, as much as movie maker.

In Winter 2010, as I was preparing for a presentation at the Ann Arbor District Library in March that compared his work to that of Cary Loren, I asked Jimm Juback if he had any plans for new movies:

The movie making part of me ended so definitively. I don’t make movies anymore; don’t really have the desire or have a voice about it in today’s world. And other than seeking out other peculiar movies, some from the same period, the film interest seems distant.

◊

All screenshots © Jimm Juback 2012

Mike Mosher is Professor, Art/Communication & Digital Media at Saginaw Valley State University in Michigan. He has contributed to OTHERZINE, Bad Subjects, Leonardo Reviews, Smokebox, often on Michigan culture. He was a community muralist in San Francisco in the 1980s and did onscreen graphics in Silicon Valley in the 1990s. Mike’s own videos and films in Super-8mm and 16mm were shown at Artists’ Televsion Access gallery in 1996.