Underworld Cinema: An Interview with J.X. Williams

by Noel Lawrence

Click here for printable version

If J.X.

Williams is one of the best kept secrets of American cinema, it's because

he wants it that way. Obsessively secretive and skillfully elusive, he

has kept out of the public eye for almost twenty years (the last known

photograph of him was taken in 1985) and, not surprisingly, he has not

done an interview for decades. Despite his impressive filmography and

some recent attention in Europe, J.X. Williams has managed to remain fairly

obscure. A Google search only returns a couple of references. Nexus does

not reveal much either. Most of what I have found on Mr. Williams has

come from old newspapers and from the old man himself.

If J.X.

Williams is one of the best kept secrets of American cinema, it's because

he wants it that way. Obsessively secretive and skillfully elusive, he

has kept out of the public eye for almost twenty years (the last known

photograph of him was taken in 1985) and, not surprisingly, he has not

done an interview for decades. Despite his impressive filmography and

some recent attention in Europe, J.X. Williams has managed to remain fairly

obscure. A Google search only returns a couple of references. Nexus does

not reveal much either. Most of what I have found on Mr. Williams has

come from old newspapers and from the old man himself.

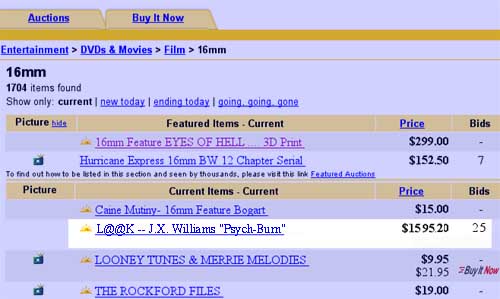

It would be impossible to tell how this interview came to be without giving a bit of background on myself. As a film scholar and curator, I often cruise the 16mm film section of eBay in search of interesting works for my collection. I especially like stag, exploitation, and other trash cinema. While I was going through the listings a few years ago, I noticed an exceptional number of bids had been made for a film called "Psych-Burn".

The winning bid was several thousand dollars... for a three minute film! Though I had no intention (or money) to buy the film, I could not resist sending an e-mail inquiry to the seller ("Sell-u-Lloyd") to find out what all the hype was about. He wrote back:

Psych-Burn is a J.X. Williams mint original. The print was struck in the late sixties with perfect no-fade color (AGFA stock). The film is almost splice free and has very little wear. Print is fully complete on a 100 ft. Reel

Lloyd

But who was J.X. Williams? After a few more friendly exchanges, Lloyd explained to me that a small but fervent cult of film collectors on eBay were searching for prints from this unknown director. He said J.X. made really weird films in the 1960's with lots of sex and gore but he handled the material with a certain finesse and craft, unusual for standard exploitation fare.

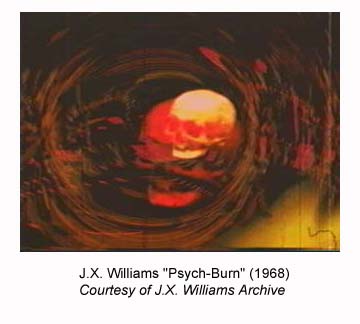

Unfortunately, the films were not available on video. As a special favor, Lloyd sent me a video transfer of Psych-Burn for a small fee and I was hooked. In the space of three minutes, J.X. pefectly captured the manic bad trip energy of the whole Manson/Altamont/Vietnam era through a phantasmagoria of garish colors, rapid cuts, and mind-blowing transitions. The film had no credits. No dialogue. No narrative. It didn't need it. It just made its point and ended as mysteriously as it began. As the reader might guess, I wanted more!

Over the next few months, I trolled eBay, film discussion boards, the Big Reel, and a hundred other places in search of other films from Mr. Williams. I made phone calls to London, New York, and even Kansas on the trail of leads of J.X. Williams' prints. Since I didn't have the money to buy the prints, I offered to rent them from collectors so I could make Betacam transfers for a hypothetical J.X. Williams' compilation tape. Collectors are a pretty paranoid sort so I got a lot of doors slammed in my face. I also had no luck tracking down the notorious features that so many talked about yet so few actually saw, let alone acquired. Fortunately, a few generous souls did lend out their prints and I soon had a pretty nifty forty minute compilation tape of shorts. None of the other films equalled "Psych-Burn" in its singular intensity but everything came pretty close to the threshold of what I consider classic cinema.

Now that I had gathered a small but substantial collection of work, I decided the next step should be to release a compilation video. I planned to make an edition of maybe 100-200 copies for other film buffs like myself. Such a tape might make enough money to pay back the money I had spent on video transfers and FedEx'ing the prints back and forth. No, I didn't have the rights but who would care anyway? I would just sell a few copies through some cult movie websites and that would be the end of it. J.X. obviously deserved better but at least people could get an idea of what was out there.

I was just about to shop for a distributor when the letter came in the mail. Fuck! It was a cease and desist letter from the estate of J.X. Williams (?!). I couldn't believe anyone could have found out what I was doing, let alone cared. Later on, I found out what happened. In one of my newsgroup postings on the IMDB, I had mentioned that I was planning to distribute his work on video. The post somehow caught the attention of Mr. Williams' attorney and my traitorous ISP readily handed over my contact information to him.

I made my position very clear to the attorney. Given the fact that I stood to make so little money from the tape anyway (it was just a good deed as far as I was concerned), I told him that I planned to give out the tape for free to anyone who asked. Without any money involved, I figured they had very little motivation to come after me.

A couple days later, I got a phone call on my land line at home. This was strange because the number is unlisted and only my parents and a couple close friends call me there. Most of my friends just call me on my cell. For the first ten seconds, there was dead air on the line. Just some wheezing. I was about to hang up when a deadpan voice began.

"I eat little boys like you for breakfast. Stop fucking with my films before I get hungry!".

Such was my introduction to Mr. Williams.

The conversation (or rather J.X. Williams' monologue) lasted another minute before he hung up on me. Additional calls soon followed, usually in the late evening or early morning hours. Despite my pleas, he always hung up before I could get a word in edgewise. After the second (and third and fourth) "conversations" on the phone over the next week, I finally got J.X. to open up a little. "You know, they're not going to do to me what they did to Ed Wood." he lamented quietly, a rare lull in his invective.

"What did they to do him?" "That guy put his heart and soul into his work and a bunch of little punks smoke reefer and laugh at him. Dumb motherfuckers! Why don't they go out a shoot a film? See what it's like to make a real movie."

Although I have inhaled while laughing at an Ed Wood film, J.X. Williams was no Ed Wood. Although his films have awkward moments, I really do think they hold a special, unique place in cinematic history. I said as much to Mr. Williams and a little flattery went a long way. At least, he ended the call with an actual "goodbye" rather than an obscenity.

About a week later, a FedEx passage arrived in my mailbox. Inside was a DigiBeta cassette with a hand-scribbled note:

For Volume One.

Regards, J.X.

Unfortunately, the tape was title for title exactly what I had collected for my compilation tape. During our phone discussions, I think I mentioned some of the films I had seen and he must have figured out what I had and didn't have. The fucker was holding back on me! Of course, his vague allusion to "volume one" gave me hope there was more where that came from. But who knows when I'd hear from him next...

Anyway, the transfer was pristine, far nicer than what I could afford to do. I wanted to thank him but I had no way of contacting him. The address and phone number on the FedEx label belonged to his attorney. I asked his lawyer if he could provide me a phone number but he refused. In fact, the jerk wouldn't even take a message for him! I even tried to trace the phone number J.X. used when he called me. To my disappointment, a friend at Pacific Bell informed me that the calls had originated from random pay phones all around San Francisco. This guy definitely did not want to be found.

In the meantime, I did a little more background research on Mr. Williams. As much as the Internet is a great research tool, it can't do everything. You can't find much more info on him than the screenings I had organized on his behalf and a few of his pulp novels (more on that later). Instead, I had to do some detective work off of his films. Specifically, the credits of one film identified a defunct lab in LA that developed the film. Perhaps, he was based down there.

Using my old student ID, I snuck into the Stanford University library to check out some micofiche from LA newspapers of that period. The periodicals section was still a bit behind the times but they did keep a name index in one of those old wooden card catalogs that mostly disappeared in the age of the database. I hit pay dirt. There were 10 cards with the magic words "Williams, J.X.".

Surprisingly,

I didn't find the articles in the "Arts & Entertainment" section of the

paper. J.X. Williams appeared in the police blotter! A few articles described

a botched break-in he attenpted at Twentieth Century Fox. Apparently,

this had not been the first time they caught him there and he did six

months in LA county. The rest of the articles described a car bombing

he survived. The newspaper identified him as a "notorious director of

mob-financed exploitation and pornographic films". The reporter mused

the bomb had been a mob hit in retaliation for an unpaid juice loan and/or

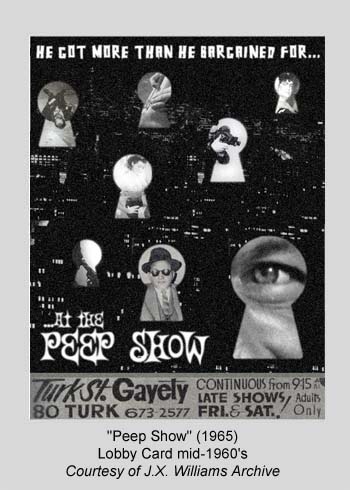

financial disputes arising from a film called "Peep Show". Peep Show!

That title raised the hairs on the back of my neck with archival lust.

Surprisingly,

I didn't find the articles in the "Arts & Entertainment" section of the

paper. J.X. Williams appeared in the police blotter! A few articles described

a botched break-in he attenpted at Twentieth Century Fox. Apparently,

this had not been the first time they caught him there and he did six

months in LA county. The rest of the articles described a car bombing

he survived. The newspaper identified him as a "notorious director of

mob-financed exploitation and pornographic films". The reporter mused

the bomb had been a mob hit in retaliation for an unpaid juice loan and/or

financial disputes arising from a film called "Peep Show". Peep Show!

That title raised the hairs on the back of my neck with archival lust.

Peep Show was the crown jewel of the J.X. Williams filmography. Film collectors spoke about it the way normal people talk about sex. I never met anyone who had ever seen it. Everything I heard was told second-hand. In fact, the film never even screened in America.1 It was a European production and had been seized by U.S. customs as obscene material. This happened in 1965, just a little before the Naked Lunch trial liberalized things a bit.

Some claimed there were still extant prints of Peep Show in Europe. I also heard that Martin Scorsese had a print in his own private collection. I actually tried to call his secretary about that once but I predictably got nowhere.

From what I heard, Peep Show was the first realistic depiction of La Cosa Nostra, produced nearly a decade before Coppola's first entry in the Godfather trilogy. It also touched upon a lot of conspiracy theories on JFK, Cuba, Frank Sinatra, and the mafia long before they had come in vogue.

Though the paper identified the dispute as "money-related", I suspected the bombing had more to do with something he showed in that film. The Chicago mob had a large stake in Hollywood. They also had heavy involvement with JFK and Cuba. Was it possible, J.X. Williams had been privy to secret information that he then used in his film? Perhaps, that was the conspiracy theorist in me talking but I had a feeling something fishy was going on. In any case, I knew this J.X. Williams fellow must have had an interesting story to tell.

Aside from these two stories, I didn't have much luck finding more. I did look at old movie listings for sitings of old J.X. Williams films. There were a few listings from the late 1960's of J.X. films that played at the Hollywood Art Theatre and a few other grindhouses. All one-week and two-week engagements. Box office poison, most likely. In the late 1970's, there also appeared to be a J.X. Williams renaissance. A number of his titles played again on the Midnight Movie circuit in Southern California. They were introduced by some guy called "The Phantom of the Cinema". I even saw a photograph of The Phantom in one of the larger ads. He was dressed up just like what you would imagine, tailcoat, plain white mask, and gray disheveled hair. Additionally, he had these big heavy chains adorned with film reels which he wrapped around his body. J.X. Williams incognito? Who knows?

Fast forward two years. I ended up giving away a few dozen copies of my J.X. Williams compilation ("Sinema" -- still available if you beg me) and had resigned myself to the fact that I wouldn't be likely to find more material on my own. Sooner or later, I reckoned some DVD label like Fantoma would probably uncover all the celluloid swag and I finally would see it in all its glory. It didn't go down like that.

Late one evening, my land line began to ring. I stumbled out of bed and picked up the receiver.

"I want to have a word with you about my films." he began abruptly, not even bothering to identify himself. He spoke as though only two minutes had passed since our last phone call instead of two years.

I kept my mouth shut and let him do the talking. He told me a number of "individuals" had died recently which allowed him to be "operate a little more openly" since our last conversation. I didn't know it at the time but these "individuals" were made guys in the Chicago outfit who had a beef with him.2 Anyway, he believed the time was ripe to begin re-releasing some of his films or, at least, the ones he could track down. Sadly, J.X. Williams didn't have much more than he sent me already. However, he did have workprints from a lot of the original features and, slowly but surely, he was reconstructing the films as best he could.

These works would be distributed by a privately-funded foundation called "The J.X. Williams Memorial Archive". "But you're not dead!" I told him. "Yeah, but a lot of people sure wish I was," he quipped. In the end, he decided to give up the phony death routine and go completely upperworld. In fact, he even asked me to do an interview with him. I was honoured but also a bit puzzled. Yes, I do edit an online film journal called OtherZine but it's really small potatoes. I'm lucky if I get a few hundred hits a month.

"Can't you do better than me?" I asked. " I mean can't you go to Film Comment or Roger Ebert or someone? Why me?".

"Trust," he wheezed.

Trust or no, setting up a face-to-face meeting with him proved to be a pain in the ass. First of all, he refused to give me a phone number, mailing address, or e-mail. I forgot to give him my cell phone number so he called the land line a number of times while I was out. Then, the meeting time got changed twice. Just as I was about to give up hope, he called me and said to meet him at a cigar shop in North Beach in twenty minutes. Even by car, that's a really long haul and my wheels were in the shop! Fortunately, I caught the buses just at the right time and made it up there with two minutes to spare (although I did forget a tape recorder in my haste).

As instructed, I asked the clerk at the counter of Cigar Store for "a pack of chewing gum". My escort led me into the back, through the storeroom and into an alleyway. Across the alley, stood an imposing pair of steel-plated doors. After fishing out one of those industrial-sized keychains with about fifty keys, he unlocked the door and we went inside. The front room was dark and dusty. Jukeboxes and video poker machines of dubious legality lined the walls. Another twenty paces brought us to a wooden door with the word "office" handpainted across the transom.

My escort gave an elaborate knock and I heard someone cough. Not a real cough. Just some kind of signal. The clerk opened the door and walked off without a word. The office was even darker than the front room. There was a chair and an end-table with an old banker's lamp. A gruff, disembodied voice told me to sit down. I did. The light was harsh and I had to squint. I complained the light was bothering my eyes. The voice replied he could accomodate me by pulling my eyes out. I then got a barrage of questions of who I was and why I came there. The whole thing was a little ridiculous but even if it was just theatre, it made me a bit uneasy.

Just as I was about to tell him to stop messing around, the old fox flipped on a light switch, revealing a rather unremarkable office with a drop ceiling. A gray-haired gentleman who bore a striking ressemblance to a very famous aging movie star approached me with a sly grin. 3

"Please forgive me. All my life, I was always the one at the end table. I wanted to see what it was like from the other side. I think you know who I am."

He had a firm handshake but his palms were cold and clammy. I felt like I was shaking hands with a corpse in an advanced stage of rigor mortis.

(What follows are my notes from a marathon interview that lasted from the afternoon into the evening. Before I proceed, I feel responsible to make some final remarks. From my experience, you need to take everything that Mr. Williams says with a grain of salt. J.X. constantly contradicts himself, changes names and dates, and gives you the impression that he is telling you less than he actually knows. Sometimes he appears to be playing some kind of mind game of which only he understands the rules and the true object. This has led to more than one rift in our relationship. All the same, J.X. is a gifted raconteur and I would like to believe at least part of what he says has historical validity. For that reason, I will transcribe the interview in its entirety.)

NL: I know that we spoke a little on your phone about your biography but I guess we should start from the beginning. How did you get started in film?

JX: I grew

up in the Boyle Heights section of LA. Very Jewish and very lefty. My

old man was a carpenter for movie sets and a major player in the CSU.3

Those were rough days. If he wasn't out of work, he was on strike. IATSE,

the rival union, hired goons from the Teamsters to break up the picket

lines. They fought dirty. He would come home bloody sometimes. And after

a long day at the picket line, he got threatening phone calls all night.

One time I picked up the phone and this guy asked me if my father was

paid up on his life insurance. My folks tried to keep me in the dark about

all of this so I thought it was a real life insurance salesman. I tell

my old man "Hey Pops! There's a guy on the phone who wants to sell you

life insurance." Of course, by the time he got to the phone, the caller

had already hung up but he knew what was going on. After that, my parents

didn't let me answer the phone anymore.

JX: I grew

up in the Boyle Heights section of LA. Very Jewish and very lefty. My

old man was a carpenter for movie sets and a major player in the CSU.3

Those were rough days. If he wasn't out of work, he was on strike. IATSE,

the rival union, hired goons from the Teamsters to break up the picket

lines. They fought dirty. He would come home bloody sometimes. And after

a long day at the picket line, he got threatening phone calls all night.

One time I picked up the phone and this guy asked me if my father was

paid up on his life insurance. My folks tried to keep me in the dark about

all of this so I thought it was a real life insurance salesman. I tell

my old man "Hey Pops! There's a guy on the phone who wants to sell you

life insurance." Of course, by the time he got to the phone, the caller

had already hung up but he knew what was going on. After that, my parents

didn't let me answer the phone anymore.

My dad was a tough son-of-a-bitch. He was fearless and, despite the booze and the belt, I really admired the guy. He stuck with the union until the bitter end. After he got blackballed, he ended up as a delegate for the ILWU but that's another story. NL: But how did you get started in film?

JX: Well, I was getting to that. You see, a nice Jewish boy like me had two career choices: doctor or lawyer. About the last thing my folks wanted me to do was to get involved in the movies. Now, at this point, I am supposed to tell you how I fell in love with the movies when I saw my first Marx Brothers film. However, it didn't go down like that. And most film guys who give you that line are lying.

I think it all started with puberty. You realize there is this whole world of beautiful women, expensive mansions, fast cars, glamour and glitz AND YOU ARE NOT PART OF IT. And of course, the center of that mythical world in mid-century America was Hollywood. That's why I wanted to be in pictures.

By eighth grade, I had lost most of my interest in a formal education. Most of the time I was dodging truant officers to go to the matinee. I got my education in the movie palace. Lost my virginity there too just like the Pauline Kael book.

A lot of people dream about working in pictures but, lucky for me, Hollywood was in my backyard. I quit school when I was fifteen but don't think I was a JD. I knew exactly what I wanted to do with my life. The first day of summer vacation I walked right into the employment office at RKO and asked for a job. They had Citizen Kane and film noir so that was where I wanted to be.

I must have looked like a real idiot when I came in there. I wore my only suit which was left over from my Bar Mitzvah when I turned thirteen. It was now two sizes too small and I could barely fasten the top button of my dress shirt. The collar had a lot of starch and it was like torture on a hot summer day. Not surprisingly, they laughed me out of the office but I didn't give up so easy. I came back again and again until they got so tired of my face, they gave me a job in that holy of holies, the mailroom. Now I don't want to bore you with a long exposition on the workings of the mailroom so I'll give you the Cliff's Notes. Before the age before e-mail, you could find out just about everything about a studio in the mailroom.

That is, if you knew how to snoop around without getting caught. There were old timers back there who knew more about how a production was going than the suits in the boardroom. Don't think it was easy though. Opening sealed letters is a fine art form and it took me a long time before I really got good at it. Also, the studio was more careful with the juicy stuff. The executive secretaries used this special kind of tape that was really hard to peel off without ripping the envelope flap. Fortunately, one of the older guys took me under his wing and showed me the tricks of the trade. Within a few months, I had the place clocked. I knew every last assistant vice-president and bean counter. I knew who was on vacation and if they were going up, down, or into the street. I even knew the kind of perfume Howard Hughes' secretary wore. Invaluable information for bribes. Of course, I wasn't just learning this trivia for fun. I had plans.

Since my cheapskate parents wouldn't spring for a 8mm camera from Sears-Roebuck, I had to figure out something else to do with the movies. Paper was cheap so I started writing scripts when I was twelve. Mostly stupid Robinson Crusoe type crap. All of that changed one fateful day in the mailroom when I was doing a "sneak and peak" on some outgoing mail.

I opened a letter which had an invitation to an advance screening of Fyodor Otsep's new film "The San Francisco Story".5 The letter said a pair of tickets were enclosed. However, someone had mistakenly put three tickets in the envelope. So guess what? I got a new starched shirt from Ward's and showed up at the theatre at 8 PM sharp.

I was hoping that I would get to sit next to some hotshot producer or an aging starlet with a penchant for young boys. Unfortunately, I did not get my big break that night. In fact, so few people attended the screening, I practically had an entire row of seats to myself.

I didn't get my big break that night but I got something better -- cinema as a true art form. It was a hard-boiled, mercilessly realistic story of a teamster who agitates against union corruption. It was a great film. Not just great. Real. After a year at RKO, I knew a little more about my father's union activities and the truth behind the "carpentry accidents" that sent him to the hospital.

That night was my vision at the crossroads.

NL: I'd love to see that film. Can I find it on video?

JX: Nope. It was never released. Hughes killed the picture.6 He had just taken over RKO and he couldn't stomach the leftist slant of the film. Most likely, he sabotaged the advance screening which accounted for the poor attendance. Further, Otsep was Russian and that automatically made him suspect in those days. That was his last picture. He passed away about a year later. The poor old man probably died of a broken heart. Anyway, I reckon two people walked away from the theatre that night with a sense of awe and inspiration. One of them went on to write a script that became a critically acclaimed film starring Marlon Brando. The other one didn't do quite as well.

Within a week, I wrote a script called "Hollywood Confidential". Now there's a memorable title! It was just like Otsep's film except that I replaced the dockworkers with the craft unions in Hollywood. I don't know what I was thinking when I wrote that screenplay. Even if it had been any good, no studio would ever green light a project about labor struggles in Hollywood. Pathetic as it was, however, it wasn't bad for a sixteen-year old. At least, I was groping my way towards social consciousness. Around this time, a really juicy memo was making its way around the mailroom. I never saw it firsthand but all the senior mailroom guys were talking about it. Bear in mind, these were the days of HUAC and the Hollywood Ten. Hughes decided to do some preventative maintenance and hired some detectives to investigate communist infiltration at the studio. The end result was a list of names of various actors, scriptwriters, and directors suspected of ties to the CPUSA.

So I took a chance which changed the rest of my life.

(End Part 1. To be continued in next issue of OtherZine)

1. Actually, the film screened briefly in San Francisco in 1966 after J.X. Williams rented his personal print of the film to a stag movie theatre in the Tenderloin. (More "respectable" theatres had refused to screen it). According to Williams, the box office tally was about $26 during its one-week engagement and the film was quickly replaced by more standard nudie-cutie fare. back

2. This conversation occurred very shortly after the death of Lew Wasserman. I later asked J.X.. if there was any connection between his "coming out" and the demise of the MCA mogul. He was non-commital and changed the subject quickly. back

3. For reasons of anonymity, J.X. Williams requested I not specify the actor in question.back

4. The Conference of Studio Unions (CSU) was a splinter union that broke off from the established International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE). The CSU took a harder line against studio management and vigrouously protested the mafia influence and widespread corruption within IATSE. As the CSU became larger and more popular, IATSE branded the union as "Communist-dominated" and began a campaign to discredit them. This conflict culminated in a number of large-scale riots in which IATSE strikebreakers in collaboration with the LAPD attacked CSU picket lines For more information on this period, Mr. Williams recommends Dan Moldea's "Dark Victory" as a good introduction (Penguin Books, 1986). back

5. Not to be confused with the 1952 picture of the same name. back

6. J.X. said on another occasion "I spent years trying to track down that film. From what I hear, the negative was either lost or Hughes might even have ordered it to be destroyed."back