We are all spied upon, archived, forgotten. What are the new meanings that define this aesthetics of experience? What are the aesthetics of framing– ‘that contained within the experience’. If the film-maker has become the creator of experiences, what is to be ‘contained within’ the experience?

With Virtual Reality the décor is that constructed with the tools used to generate the content for the experience for the user/viewer. The entirety of this experience is likely to have been either recorded from an experience in the world using 360-degree cameras such as the Go Pro mounts that resemble cubes with cameras facing every direction, or generated using 3D CGI and game engine created imagery.

Contemporary visual culture increasingly embraces and celebrates the notion of complete “experience”. Just as the panorama of the 19th century enveloped the visitor in a 180-degree scene, today’s virtual reality and augmented reality seek to provide a complete, enveloping, melding of data, audiovisual information, sight, sound, and the concurrent real-time combination of these with everyday activity. The world is pregnant with buildings, streets, people, and objects supposedly seamlessly integrated with their data and their own archives, yet ironically the more connected subjects are, the less in touch with each other the same subjects appear to be. Populations have never had more connectivity, yet have never more resembled disassociated zombies of retina touchscreen distraction.

Drones, the so-called Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligences now mediate everything. Spies, spooks, whistle blowers and nefarious actors hide in the shadows or “bare all” for download in the bright light of accountability. Data is not just a fact of contemporary life for anyone participating in the western world, it is a requirement, an obligation. Augmenting one’s experience is rapidly becoming the domain in which aesthetics is unfolding as well. Where the screen and the stage once framed ‘that contained within’ or ‘mis en’, now the entirety of experience itself is the framework of the act of aesthetic organization.

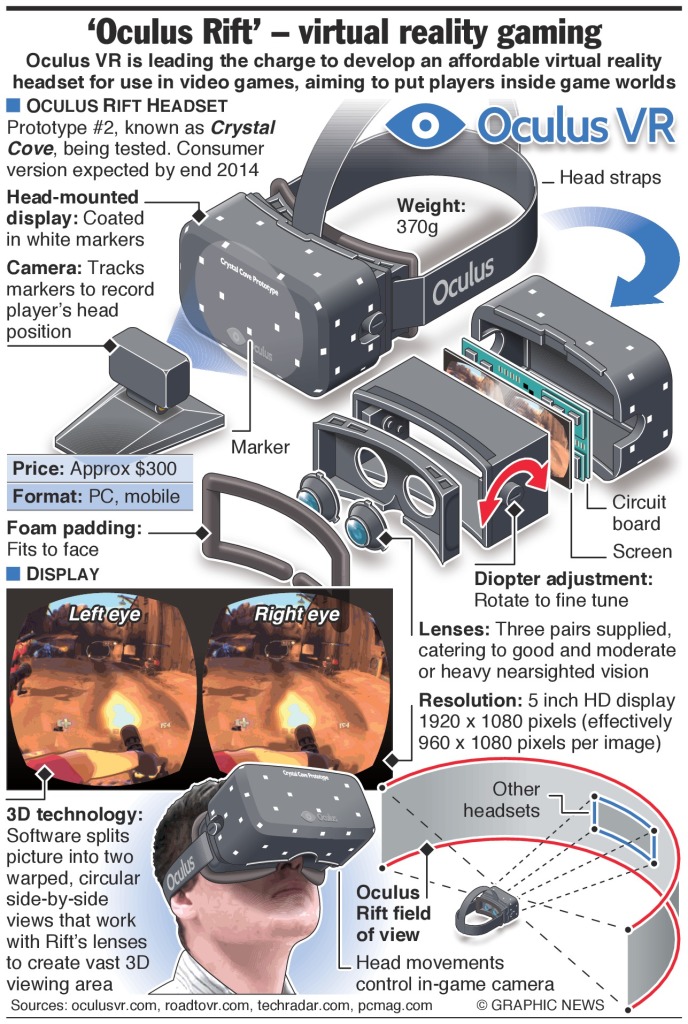

Oculus Rift brochure from 2014 showing a cutaway of the crowd-funded head mounted display unit later bought out by Facebook.

At a Virtual Reality film-making conference recently, I heard panelists talking about ‘in-sphere’ and ‘out-of-sphere’ as a correlate for ‘in-frame’ and ‘out-of-frame’. The sphere, or rather that fishbowl-like region into which our heads and sensibilities are placed when we put on a head-mounted display such as Oculus Rift or Google Cardboard is the ‘stage’ where ‘mise-en-experience’ takes place.

VR experiences may be recorded using 360-degree cameras, or constructed using tools such as the game engine UNITY and UNREAL. In such cases, the viewer is expected to remove herself from the ordinary experience of life and cross over into a documentary, fiction or some such combination of the two. Either way in this artificial panoramic realm, the notion of the ‘scene’ presents new ways of being considered.

The geo-spatial world around us unadorned might, with Augmented Reality or AR and wearable computers for example, be added onto with audiovisual and data features pertinent to locale, the viewer’s history, her trajectory though time and space, her sense of her self in relation to others likewise ‘connected’. Head mounted displays, wearable computers, and technologies that meld the past with the present, the physical with the nonphysical are coming in fast. Sensors scan everything. Metadata about metadata joins a sea of associations in a never-ending flowchart of patterns of ideas. A vast intricate spiderweb universe of everyone sharing everyone’s secrets and banal facts, all visual, all sensed, all parsed by algorithms is envisioned. I can put on my headset and see objects all around me. And yours. And you mine. We can share it all.

The concept of ‘that contained within the scene’ in terms of virtual reality encompasses the user’s “own” sense of the entirety of experience. When she puts on the Oculus Rift headset she is really gaining a sense of the totality of everything around her that is placed within the same realm, much as she would experience a place if she were a tourist on holiday. What she is being invited to understand and enjoy and appreciate is the experience. And with the VR/AR she is able to see and listening to everything that she is experiencing.

Like Videogame designers VR experience designers are looking to create something that is “in the round” , not only recorded in the audiovisual sense but also in what we might call the experiential surround. Virtual Reality experience designers are looking to create experiences that literally encapsulate the entirety of being-in-the –moment. VR cameras are like any other cameras and can only be placed in certain locales. One can jump cut from one camera to another. Cameras can move. Users often complain about motion sickness, but that is a discussion for another time. The point is the extensive spherical scope of VR and its ability to make the scene into experience and visa versa.

Beyond the simple documentary nuances of the everyday that people might undergo in the course of the average day, VR can record the sense of what it was like to inhabit a place. Instead of a framed shot, we might now be said to be gaining a sphered shot .

When the camera is moved so is the experience of moving the whole eye-and-head-platform such that all around can be seen as the act of the camera is moved. CGI and ‘reality’ can be combined such that for example, when one looks up and looks down its possible for the ‘ground’ to appear to be actually giving way, or for the ‘sky’ to splinter into pieces. Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality designers are really looking to create personal moments and situations.

‘Mise-en-experience‘ is about planning and considering the inclusion of every aspect of the virtual immersion event. Just as Banksy felt he could best articulate his disillusionment and anger at the dismal world of today with the theme park art installation Dismaland, such a gesture also might have been accomplished using Virtual Reality.

According to game designer Scott Rogers,“Everything I learned about game design I learned from Disneyland”. In both Disneyland and Dismaland there are “weenies”– central architectural features like the princess castle and the Matterhorn that attract the viewer to them – large structures that attract the user/viewer/visitor. There are meaningfully placed paths between these attractions. And it is the path-ing as much as the ‘weenies’ that determines the effectiveness of the experience. The VR/Game/Theme Park/Art Installation designer is the designer of “the dynamics of being there”. The designer of what we might call the ‘dance of the user’ in their imaginary place, the sense of motion through that place.

This complex and dynamic relationship between the user and her environment, the relationship of that use to other users in a shared space is of course ‘cybernetics’, identified by Norbert Weiner in the 1940s. But in terms of VR and its effects on people as they move around and manipulate their 3D VR avatars online in real time, it is also what Jaron Lanier in the early 1990s used to describe as body music; the post symbolic language of user’s gestures. This, too, is part of ‘mise-en-experience‘.

Why place objects in a virtual scene and limit oneself to the rules that govern physics and expectation in the normal world? Why use natural boundaries or spatial boundaries in the way they would normally apply at all?

Lessons learned from game design, architecture and urban planning, dance and other arts, which involve time space and motion can assist here. From games comes the notion of the spatial and temporal boundary. Placing limits on where a person can go in order to manage the experience, but also to manage memory (computer memory, not human memory). Temporal constraints – time limits can help frame the sense of there being goals, challenges and rules, bringing VR within the context of ludology. What is the victory condition? Then there is the field of music; the mathematical breaking down of time into fractions where the control of air pressure notation wave forms overtime is also part of the general sensibility. VR and AR can borrow from music, the patterning of events over time to create a sweep of moments, much the way the great composers arranged events to create emotional tones. Consider the VR experience that is the Beatles’ White Album, each song a mini-movie or VR scene, complete with characters, settings, events.

Bubl camera – Kickstarter funded 360 degree camera used for consumer-level VR photography and film making.

VR and AR aesthetics borrow heavily from cinema itself particularly animation with its fractious breaking down of time into the individual frame. It’s not by accident that many Virtual Reality movie productions are made using the same tools often used in video game design such as Unity and Unreal. Both of these tools allow for the creation of 3D models elsewhere, in resources like 3DS Max and Maya where they are also animated, and for these to be imported into experiences that may well share the ‘sphere-space.’ Views of the real world can thus be meshed in experience with unique imported objects.

At the VR conference in San Jose this year, a panel on VR film making emphasized the ‘problems of nausea’. As VR goes mainstream, the rush to find a way to commercialize it as an extension of cinema or a kind of ‘cinema-in-the-round’ does little to understand the medium’s origins in the research labs of the late 1970s and early 1980s. Back then, the desire to use the medium to discover entirely new categories of experiences was more the goal. But since the economic lure of mainstream entertainment is both risk averse and extremely strong, pundits would sooner see a return on investment by retooling VR for already proven genre fiction uses (Space Marines, Extreme Sports, Adventure Heroes in the 3rd World) than dare to take a chance on something that genuinely breaks the mold. But we shall see. Perhaps there will be a paradigm shift, a new group of experiences which will emerge that will bring us the Bruce Conner of VR, or the Brothers Quay of Augmented Reality.

It could well be that the massive archives of existing film merge with the online databases in the development of new hybrid media forms. A digitized future lies in how truly creative and experimental filmmakers and VR designers will combine these worlds.

CASE STUDY – Archival footage from 8 years ago about where I am on this street corner in San Francisco is being superimposed over my view of it it now. I can walk to the very same spot to see where it was filmed from the very same angle.

Like Dziga Vertov, I am “Kino Eye”, all over again. All the information about the conditions on that day are available to me and all those about today, too. And all the people in the footage. And their relatives. And all the other people who have seen the footage. And what they thought. And what I think. And on and on and on. Then there is the 3D data about the buildings and the pipes under the road; the flight patterns of the planes above.

LINKS:

Dactyl Nightmare – VR arcade game

Interview with Morton Helig https://www.youtube.com/watch?

_rear.jpg)