by Anna Spence

Currently, our understanding of cinema relies on the moving image’s capability to transport its viewer away from a space of its presentation, into an imagined cinematic world, built through the collaboration of viewer and filmmaker. But what might invite greater meaning beyond the rationale of narrative convention? Something more generative and less passive?

In “Film Image/ Electronic Image: The Construction of Abstraction, 1960-1990” author, and curator John Hanhardt discusses a select body of film and video works which redefine the moving image through exploring issues of abstraction. In this piece, Handhardt writes about Bill Viola’s 1973 work, “Information”, which Viola created by accident, by feeding a videotapes output back into itself.

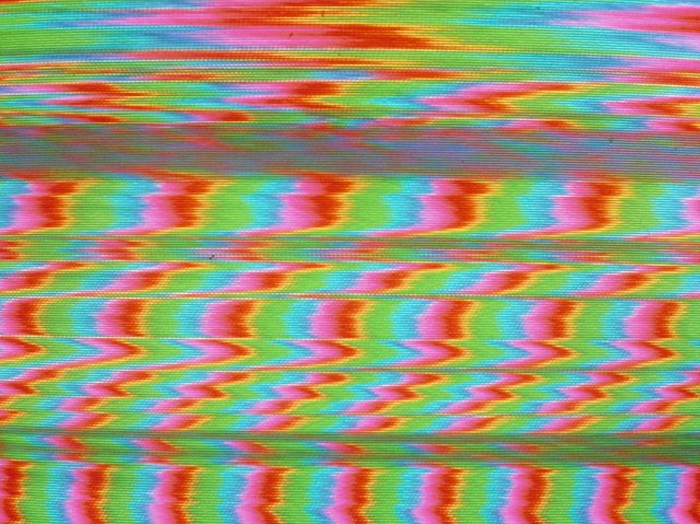

Bill Viola has been instrumental in the expansion of video art as a viable medium. A new media artist, Viola expanded the scope of video art within the realms of technology, historical research and critical discourse within his decades-long career.1 Today, Viola’s work can be found in distinguished collections. In addition to his artwork, his writings have been extensively published and translated for international readers. “I went through an early infatuation period with the technology; I obliterated it — literally and metaphorically.”, 2 Viola recalls.During this time, he created “Information” [1973], a work which utilizes analog feedback to investigate potentials inherent to the video signal. Viola describes this work as “…the result of a technical mistake made while working in the studio late one night when the output of a video tape recorder was accidentally routed through the studio switcher and back into its input. When the record button was pressed, the machine tried to record itself. “ (Viola, p.25). The tape’s non-conforming (or corrupted) video signal creates random patterns of noise and interference, which is interpreted differently by every video player it encounters. For this reason, “Information” will never play the same way twice.3

By 1973, video art was teetering on the cusp of becoming an entity independent of avant-garde cinema 4, and on some level this must contribute to the difficulty of assigning “Information” to any one genre. On one hand, “Information” cuts through what avant-garde filmmaker Peter Gidal calls “this miasmic area of ‘experience’”, allowing the moving image to “…proceed with film as film.” (p.2), or video as video for our intents and purposes. However, since the tape signals have been given an agency uncommon to

video, it can also be discussed in terms of its materiality. Regardless, “Information” demonstrates video’s ability to traverse within and beyond the borders of convention, both cinematic and artistic.

Forty-three years after the creation of “Information”, how might one embrace error, bring the materiality of the video to the forefront, and do so through the use of current video production technologies? Reflecting upon Viola’s artistic process in the making of “Information”, one might conceive of the moving image as a visible trace of a silent conversation between machines. And while the political, cultural and technological landscapes which produced “Information” have long since vanished, Viola’s embrace of

error finds a spiritual successor in the glitch art movement.

In “Glitch Studies Manifesto”, artist and theorist Rosa Menkman describes a glitch as an unexpected break within the flow of technology. Glitch undermines the straightforward presentation of an image and how it is perceived. The difference between intent and reality opens up a void which disrupts up the transmission and perception of flow. It may seem logical to conclude that this void signals the destruction of an image. However, Menkman argues that what it presents is a space for the viewer to

bring their own interpretations, logic and experiences.5

Materiality serves as a common ground for “Information” and glitch alike. Ostensibly, glitch is a creative practice that engages primarily with error . But, like “Information”, it relates to the materiality of moving image. The faltering video betrays itself by magnifying its own mechanisms, thus establishing an overlap between error and materialism. But exposing its materiality opens up possibilities to explore what has yet to be seen, a dynamic and urgent experience which calls the mechanisms of film production

and presentation into question.

Within the context of materiality, both also serve to dispel the myth of artistic genius. In particular, “Information” directly contradicts Art Critic Rosalind Krauss’s theoretically sound-albeit-dated notion of the narcissistic video artist, which she describes in her article, “Video Art: The Aesthetics of Narcissism”.6

As we look at the artist sighting along his outstretched arm

and forefinger toward center of the screen we are watching,

what we see is a sustained tautology: a line of sight that

begins at Acconci’s plane of vision and ends at the eyes of his

projected double. In that image of self regard is figured a

narcissism so endemic to to works of video that I find myself

wanting to generalize it as the condition of the entire genre.”

(p.180)

Decades later, performance artist Jeremy Bailey asks, “What happens to Krauss’s narcissism in the presence of this new machine culture?” 7 Citing Roland Barthes’ “Death of The Author”, Bailey concludes that, “…the Author becomes a Reader, pathetically trying to peck out an understanding of her or her own fantastic creation. Here, the only narcissist is the unwaveringly confident machine…” (p.127).

In some sense, “Information” serves as a premonition of the future. That it was created five years before Krauss’ writing contradicts her understanding of video art as inherently narcissistic, and hints at the rise of Bailey’s notion of machine culture. In the Winter 2016 issue of October Magazine, David Joselit, Carrie Lambert-Beatty and Hal Foster ask, “What are the risks in assigning agency to objects; does it absolve us of responsibility or offer a new platform for politics?” in his embrace of error, Viola relinquishes artistic control to video signals, which manifest themselves as video static engaged in a process of perpetual transformation. “Information” flirts with this issue of risk, hinting at the possibility of post-humanism.

Abstraction seems to define this time period in a fashion that extends beyond the social, political, economic; inserting into ways which relate to the way we conceive of the moving image, and to some extent, to the way we conceive of ourselves. 8 Writing for the Brooklyn Rail, Artist and writer Judith Barry speculates that the differences between media will become harder to distinguish as they collapse into the digital realm. 9 As a result, (or because of this) the relationships that viewers establish with various modes of media presentation are becoming less tangible.

How will these issues of materiality shape our future understanding of cinema, of video art, of the moving image at large? The ability to effortlessly circulate data means that what the digitized moving image loses in substance, it gains in speed. How has this already transformed the relationship between moving image and viewer? Looking toward the future, does the possibility of post-humanism dictate that the distinctions between people and objects will inevitably fade? If so, how would the introduction of the autonomous object transform the relationship between moving image and viewer?

Notes:

1 Viola, Bill. “Biography.” Biography. N.p., n.d. Web. <http://www.billviola.com/biograph.htm>.

2 ” Bill Viola.” Bill Viola. Journal of Contemporary Art, n.d. Web. <http://www.jca-online.com/viola.html>.

3 Hanhardt, John G. “Film Image/ Electronic Image: The Construction Of Abstraction 1960-1990.” Abstract Video : The Moving Image in Contemporary Art. 25.

4 Hanhardt, John G. “Film Image/ Electronic Image: The Construction Of Abstraction 1960-1990.” Abstract Vide o: The Moving Image in Contemporary Art. 25.

5 Menkman, Rosa. The Glitch Moment(um) (2011): n. pag. Network Cultures. Institute of Network Cultures, 2011. Web. 2 Feb. 2016.

6 Krauss, Rosalind. “Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism.” Video Culture: A Critical Investigation.

Rochester, NY: Visual Studies Workshop, 1986. 179-91. Print.

7 Bailey, Jeremy. “Performance For The Computer”. The Moving Image. N.p.: MIT, 2015.. Print

8 Lind, Maria. “Introduction.” Introduction. Documents of Contemporary Art. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2013. p.16

9 Barry, Judith. “Judith Barry.” The Brooklyn Rail. N.p., 5 Mar. 2015. Web. 22 Apr. 2016.

Images are stills from “Information” by Bill Viola, 1973.

A favorite glitch of mine is when a film jams in the projector gate and then melts from the heat of the projection lamp (or carbon arc light) before the eyes of the audience. In most instances, particularly with 16mm film, it is not needed to splice out the melted frame as long as it doesn’t ruin sprocket holes. It is just left in to be projected with no one noticing it as it is just one frame of the 24 frames per second. It is just a ghost image of the once live event.

To Brilliant Anna,

a title for our future show” Urgent Experience”

Nanc